Talia Boylan

If you find yourself tasked with teaching a Great Books class (and if you have a Classics PhD, the odds that this will happen at some point in your career are relatively high), you might find yourself wondering where the idea for such a class came from in the first instance. The following paragraphs aim to shed some light on this question by tracing the concept of Great Books from the transatlantic milieu of the Victorian period to its 20th- and 21st-century instantiations in the United States, in both popular culture and higher education.

The Origins of Great Books: 1869-1920

The idea of Great Books first took shape in the second half of the nineteenth century in England and the United States. “Great Books” originally referred to lists of literary works that were thought to broaden the mind and improve a person’s sensibilities. They were conceived as a reaction to the hyperspecialized knowledge propagated by modern research universities. Notable examples include Sir John Lubbock’s one hundred best books, The Harvard Classics, compiled by Harvard President Charles W. Eliot (also known as “Dr. Eliot’s Five-Foot Shelf of Books”), and the Loeb Classical Library, which provided facing English translations of ancient Greek and Latin texts (Lacy [2006] 1-4, 27-58).

Great Books courses were invented in the United States, where public school enrollments and public libraries were on the rise. The first of these was Charles Gayley’s 1901 Great Books course at the University of California, Berkeley (Lacy [2006] 60). From Berkeley, the Great Books trend spread to Columbia, where it found an ardent supporter in John Erskine, a renowned English scholar, among others (Chaddock [2012]). In the aftermath of World War I, Erskine established a Great Books program for the 12,000 American soldiers waiting to return home from France at the behest of General Pershing (“keep their minds busy, or they’ll concentrate on girls and cognac”) (Beam [2008] 18). Upon returning to Columbia, Erskine set about implementing a great books course at Columbia called “General Honors” (ibid. 19).

New York, Chicago, and Annapolis: 1920-1948

Enter Mortimer Adler, arguably the single most significant figure in the story of the development of the Great Books phenomenon. The son of a jewelry salesman from Washington Heights, Alder dropped out of high school to work as a copyboy in the editorial room of the New York Sun (Lacy [2006] 89; Beam [2008] 94-95). While taking night classes at Columbia, he encountered the work of John Stuart Mill, whose intellectual development he envied. Inspired by Mill, who could read Greek by age three and knew Plato’s dialogues by five, Adler became enamored of the Socratic method of questioning and persuaded his friends to engage him in dialectical exchange (he later recalled: “I have it on the testimony of my sister that I was a difficult child”) (Beam [2008] 16).

Adler later enrolled in Columbia College, where he subsequently persuaded a PhD in psychology (ibid. 101). While co-teaching General Honors with Mark van Doren, he learned a distinct method for teaching Great Books classes whose influence can still be seen today: class was to be conducted around a large seminar table; classes were to be-co taught by non-experts; texts were to be assigned in their entirety in English translation; and opening questions were to be designed with a view to guiding the class discussion (ibid. 109).

While the Great Books were taking off at Columbia, Adler and others endeavored to introduce them to the general public by implementing free Great Books classes around New York City at venues such as the People’s Institute at Cooper Union, churches, YMCAs, settlement houses, and private homes. Adler himself co-taught a class entitled “Renaissance and Modern Thought” at a church on East 34th Street with the Soviet Spy Whittaker Chambers (ibid. 21-22).

In 1927, Adler met Robert Maynard Hutchings, the dean of Yale Law School, who later became the president of the University of Chicago (U of C), where he employed Adler. Both men were committed to implementing Great Books-style education at U of C and in the broader city of Chicago (Lacy [2006] 124-36). The latter endeavor led to the creation of the “Great Books Foundation,” which was funded with money from the University of Chicago and the philanthropist Paul Mellon. The rise of the Great Books movement in Chicago was roughly contemporaneous with the development of a four-year Great Books curriculum at St. John’s College in Annapolis, which also received funding from Mellon (Beam [2008] 54).

The Heyday of Great Books: 1952-1968

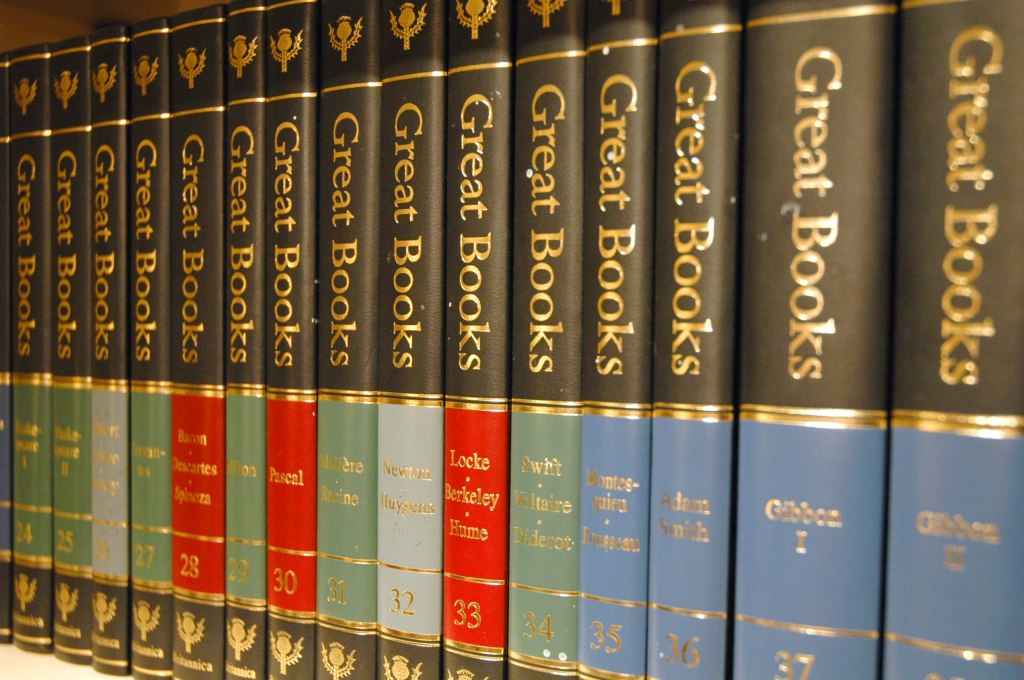

The Great Books movement enjoyed unprecedented success during the Cold War era, causing an editor for the Ladies’ Home Journal to assert that it had surpassed Alcoholics Anonymous in popularity (Beam [2008] 53). One factor that contributed to its growth was Adler and Hutchins’ collaboration with Britannica, which published a series entitled Great Books of the Western World. The series, which, as Adler boasted, surpassed the 60 inches of Eliot’s Harvard Classics by a good two inches, wasaccompanied by a hefty general index called the Synopticon that keyed 102 “great ideas” to particular passages included in the series (Lacy [2006] 179; Beam [2008] 60). The movement spawned various Great Books-themed TV and radio shows, including The University of Chicago Roundtable and Clifton Fadiman’s radio show Information Please (Beam [2008] 58).

The popularity of the Great Books in the 50s can be explained by several factors: the booming consumer culture of the growing middle class in the wake of World War II; the GI bill, which enabled demobilized troops to seek educational opportunities; and, related to this, the growing enrollment of Americans in higher education. In addition, the timeless ideas that the Great Books supposedly contained were thought to offer an antidote to the materialism of fascism and communism (ibid. 57-58).

The Great Books: 1968-Present

The Great Books movement began to decline in the 1960s. The canon of predominantly white, male authors it celebrated clashed with the recognition of non-white, non-male identities that came about in consequence of the Civil Rights and Women’s Rights movements (Lacy [2006] 261-94). The rise of TV, moreover, led to a decline in reading across the board, and the academic establishment had begun to attack the movement for its amateurish approach to literature and philosophy. Increasingly, the Great Books came to be associated with right-wing elitism. Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind (1987), for example, was construed as a vindication of the Classics for conservative ideology (Beam [2008] 91-105). The movement had come a long way from the left-leaning populism that characterized Adler’s and Hutchin’s efforts to introduce the Great Books to the general public, leading ultimately to the latter’s interrogation by the House Un-American Activities Committee (ibid. 151).

Today, Columbia and the University of Chicago both have “core curricula,” a set of required round-table seminar courses on Great Books that all undergraduates are required to complete within the first two years of their degree. St. John’s remains the only institution of higher education whose entire curriculum is devoted to the study of Great Books. Many universities and colleges, however, have Great Books survey classes that students may elect to take, and Great Books discussion groups exist in various cities and towns across the United States, though on a smaller scale than in the 1950s.

Select Bibliography

Adler, A. 2020. The Battle of the Classics: How a Nineteenth-Century Debate Can Save the Humanities Today. Oxford.

Beam, A. 2008. A Great Idea at the Time: The Rise, Fall, and Curious Afterlife of the Great Books. New York.

Carnochan, W.B. 1998. “Where Did Great Books Come from, Anyway?”, Stamford Humanities Review 6: 51-64.

Chaddock, K. 2002. “A Canon of Democratic Intent: Reinterpreting the Great Books Movement,” History of Higher Education Annual 22: 5-32.

———. 2012. The Multi-Talented Mr. Erskine: Shaping Mass Culture through Great Books and Fine Music. New York.

Lacy, T. 2006. “Making a Democratic Culture: The Great Books Idea, Mortimer J. Adler, and Twentieth-Century America.” Diss. Loyola University, Chicago.

Menand, L. 2021. “What’s So Great About Great Books Courses?”, The New Yorker Dec. 13, 2021.