James F. Patterson

A teacher should know not just how a topic is taught but why the topic is taught that way. It is therefore worth learning a bit about the history of teaching Ancient Greek (hereafter simply Greek unless otherwise qualified) and Latin. A classics scholar should find this unsurprising.

Arguments today about the proper way to teach classical languages, and Latin in particular, often revolve around the distinction between acquiring a language, on the one hand, and knowing about a language, on the other. By “acquiring a language” we mean, for instance, the ability to communicate in that language effectively. By contrast, one who knows “about a language” will be versed in the rules of the language’s grammar, capable of philological analysis but not in speaking or writing. The difference is between treating the language like a living language and a fossil to be carefully examined. It turns out, we will see, that debates about this have been around in one form or another for centuries.

To what degree “acquiring a language” and “learning about a language” are in fact distinct activities in a 21st century college classroom is a topic for another conversation. Here I outline the history of classical language pedagogy to give context to the textbooks currently available on the market.

This story is likewise one of accessibility, where “accessibility” has meant different things at different times in different political, religious, and socio-economic circumstances in the larger world. What follows is as brief as it is imperfect. I simplify a lot, but if I do so problematically or omit something significant, let me know (james.patterson@yale.edu).

Antiquity

While Latin and Greek were living languages, in formal education non-native speakers of one could learn the other through a communicative approach as children. Afterwards, students turned to a formal study of grammar and literature.

Cultural and imperial circumstances in the Roman world were such that non-Greeks learned Latin. Greeks less so. Instead, Latin speakers learned Greek (Marrou, 1956: 256-258; Horrocks, 1997: 78-79; Dickey, 2016: 1-2). Still, Greeks could begin to learn Latin via short dialogues called colloquia accompanied by Greek translations. Students were to memorize these dialogues for practical use around town—how to ask someone to watch your clothes at the baths, for instance. One would learn formal grammar at a later stage. Latin grammars were written in Latin and explained in Greek to Greek speakers by a teacher (Dickey, 2016: 4-6).

Here is a portion of a colloquium (P.Berol. inv. 10582, 5th-6th century CE) with transliterated Latin on the left and Greek on the right, originally also with Coptic (Dickey, 2016: 151-152):

| Σερμω κωτιδιανους “Κοιδ φακιμους, φρατερ; λιβεντερ τη βιδεω.” “Ετ εγω δη, δομινε.” (ετ νως βως.) “Νεσκιω κοις οστιουμ πωλσατ· εξειτο κιτω φορας ετ δισκε κοις εστ, αυτ κοιεμ πετιτ.” | Ὁμιλία καθημερινή “Τί ποιοῦμεν, ἀδελφέ; ἡδέως σε ὁρῶ.” “Κἀγὼ σέ, δέσποτα.” (καὶ ἡμεῖς ὑμᾶς.) “Οὐκ οἶδα τίς τὴν θύραν κρούει· ἔξελθε ταχέως ἔξω καὶ μάθε τίς ἐστιν, ἢ τίνα ἀναζητεῖ.” |

Greeks who learned Latin typically did so for business. Aristocratic Romans learned Greek for social and intellectual reasons. In the Late Republic and Early Empire, Roman children might become bilingual, learning Greek alongside Latin with the help of enslaved Greeks. One could also use the same colloquia originally meant for learning Latin instead for Greek (Marrou, 1956: 258-264).

Formal education in antiquity was exclusive, available to the children of aristocratic families. Doubtless many learned a foreign language also by other means, especially in a linguistically diverse familial or socio-economic environment. For instance, in the 2nd century CE Apuleius claimed that Pudens, the boy who had accused him of witchcraft, “speaks nothing but Punic and what little Greek he still remembers from his mother.” (Apology 98, emphasis mine). The kid, Apuleius continues, never bothered to learn Latin.

In the Imperial Period, interest in and need for Greek declined in the Latin-speaking world. Latin translations were made of the Bible in order to make it accessible to non-Greek speakers. Jerome and Augustine both complained about its poor literary quality compared to Classical Latin:

| …I couldn’t disregard the library I had put together with great care and effort at Rome. And so, poor bastard, I’d starve myself so I could read Cicero later. After many sleepless nights, after tears that the memory of my past sins would release from the depths of my guts, I’d take Plautus in my hands. When I’d come to my senses and start reading the prophets, the simple language would annoy me (sermo horrebat incultus). |

—Jerome, Letter 22.30 (384 CE)

| Scripture seemed to me unworthy (indigna) when I’d compare it to the greatness of Cicero, for my arrogance couldn’t deal with its style, and the sharpness of my mind couldn’t penetrate its inner meaning. |

—Augustine, Confessions 3.5.9 (397-404 CE)

The writings of the Church Fathers would provide high quality literature to Christians who wanted elegance.

The Middle Ages

Language is always evolving. Once the vernacular diverges from the standard language so much that the two cease to be mutually intelligible, the vernacular has become a distinct language. Romance languages emerged from Latin over the course of the Early Middle Ages (late 5th century to 10th century). Still, Latin remained the language of the church, politics, law, and literature in western Europe. Though Latin was now a dead language in most circles, the upper class kept it alive.

Children continued to start their Latin education with dialogues. Only after acquiring some fluency in Latin were students exposed to classical authors (Most, 1962: 1). Classical texts included interlinear glosses. Of course, few students had their own texts, so learning continued to occur via hearing and speaking Latin (Woods, 2019: 4-9).

The image below is a section of a late 14th century manuscript (Biblioteca Casanatense 685, fol. 59r) with Vergil, Aeneid 4.303-309, and glosses. For a translation and discussion of this page in its classroom context, see Woods, 2019: 4-12. To explore the digital image, see here.

Due to the functional value of Latin, the language evolved throughout the Middle Ages to meet contemporary needs, especially lexically. Inevitably, the vernacular influenced the language as well. The Carolingian Renaissance (8th and 9th centuries) encouraged higher quality and increased use of Latin in the Frankish Empire (modern France, Belgium, the Netherlands, western Germany, Switzerland, northern and central Italy) and in England. This helped keep Medieval Latin from evolving further or dying out altogether. Many of our earliest surviving Latin manuscripts were produced during this period.

In the 12th century, the Toledo School of Translators diligently translated scientific and philosophical works from Arabic into Latin and other European languages. These included Arabic translations of many Greek authors long lost in western Europe. For the next several centuries, interest in applying Ancient Greek philosophical rigor to Catholic theology flourished in the form of Scholasticism with the help of these translations.

The Renaissance and Reformation

In the 14th and 15th centuries, a new interest in human and social potential called Humanism emerged, again inspired by classical thought. It put a stop to Latin’s evolution by exalting the likes of Cicero and condemning postclassical developments of the language. From this point forward, the content and style of certain classical authors would be the focus of one’s study (Bennett & Bristol, 1903: 2-3). People continued to speak and write in Latin, but now they modeled their Latinity after Cicero. As a result, a spoken and written form of the language, which we now call Neo-Latin, was born from a fossilized classical style, distinct from the Medieval Latin that evolved from Late Latin (Rigg, 1996: 76).

As for the Greek language, since the 14th century Greeks had been coming from Constantinople to Italy, where Greek literature was known in translation but no one could read the language. They were welcomed by audiences of students eager to learn. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 increased their numbers. Textbooks, if we may call them that, were Greek grammars written in Greek, explained to students by a teacher in Latin.

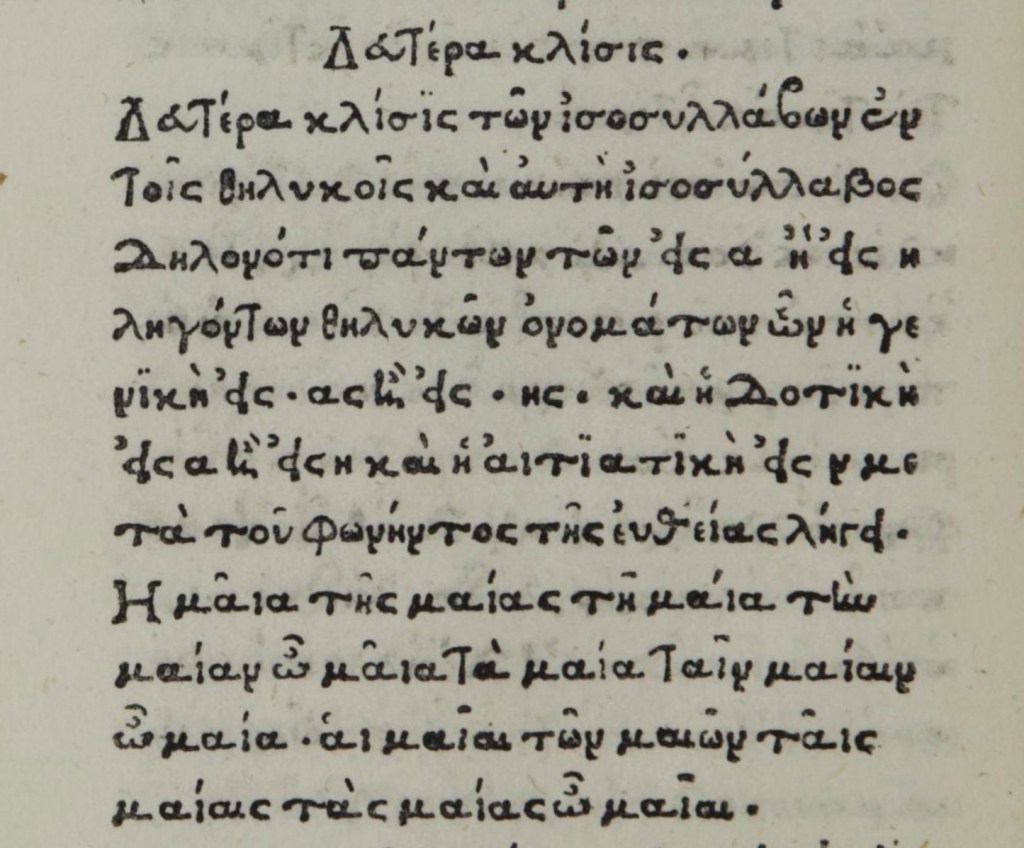

The most popular Greek grammar in 15th century Italy was Manuel Chrysoloras’ Ἐρωτήματα. In the image below, from a 1484 edition with a Latin translation, we find his introduction to isosyllabic feminine nouns with genitives in -ας or -ης. He calls these the second declension:

Initially, students were introduced to texts only after learning the grammar. Because they first encountered Greek via grammar read at them, some of the first Greek words students learned were grammatical terms. Pamphlets were circulated including the alphabet with pronunciation, tables of declensions and conjugations, and short reading passages.

The pedagogical situation improved over the next century with the production of bilingual grammars and dictionaries and elementary texts. The printing press, invented around 1440, increased the availability of these texts. Eventually students could use them to learn Greek on their own (Botley, 2010: 1-2, 71-73, 115-116).

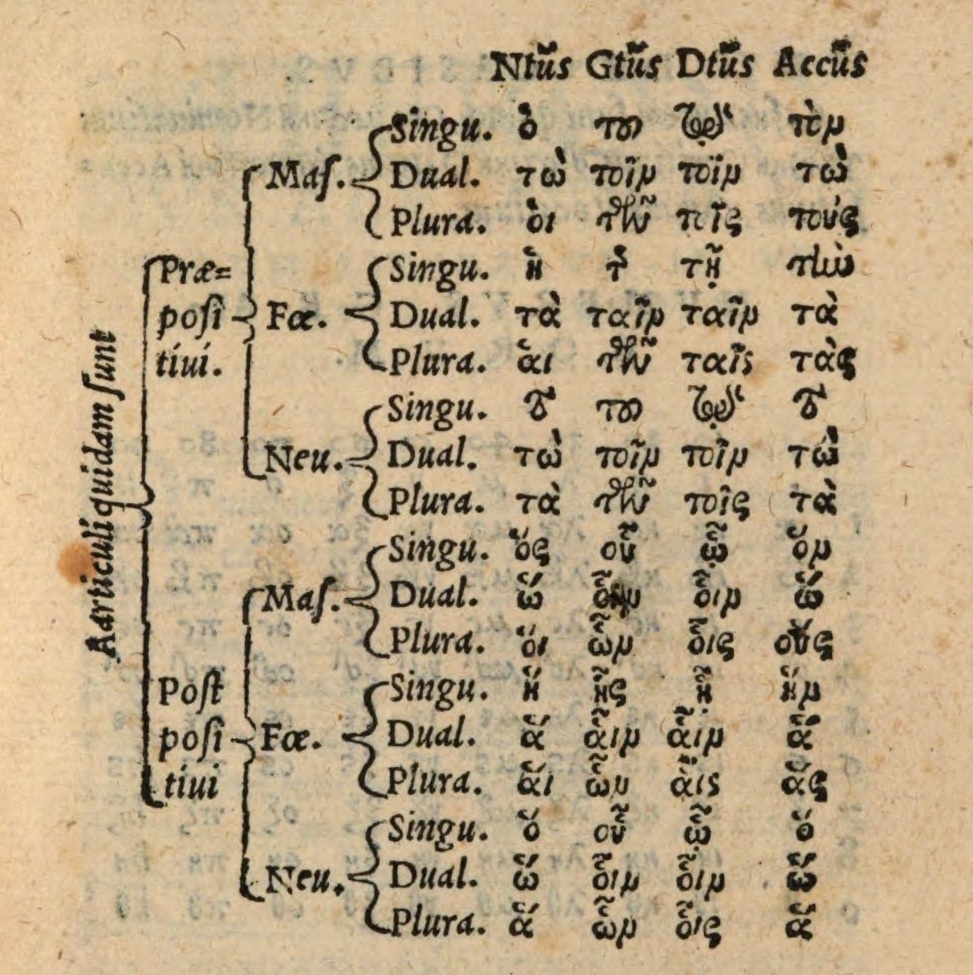

The declension of “prepositive articles” (the definite article) and “postpositive articles” (the relative pronoun) from the 1532 edition of Girolamo Aleandro’s Elementale introductiorum in nominum et verborum declinationes graecas, first published in 1509:

Scholars began to question 15th century Greek pronunciation not long after Greek reemerged in western Europe. In 1528, Erasmus of Rotterdam published Dialogus de recta Latini Graecique sermonis pronuntiatione, in which he proposed a reconstructed ancient pronunciation that we now called Erasmian. While the pronunciation of Greek and Latin often followed—and sometimes still follows—the pronunciation of a region’s vernacular, it is generally agreed that students now should learn the reconstructed pronunciation found in W. Sidney Allen’s Vox Latina, first published in 1965 (2nd edition 1989), and Vox Graeca, first published in 1968 (3rd edition 1987). Although we know that Classical Greek was pronounced with a pitch accent, most teachers still use a simple stress accent.

A motto of the humanist Renaissance was ad fontes, a call to return to the ancient Greek and Latin sources. The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century applied the sentiment to Scripture, wresting control of exegesis from the hands of the Catholic clergy. On the one hand, the Reformation decreased the role of Greek and Latin in Protestant countries (Britain and Germany, for instance) by translating Scripture into the vernacular. On the other hand, its adherence to the principle of ad fontes reinforced the prominence of Greek and Latin in education.

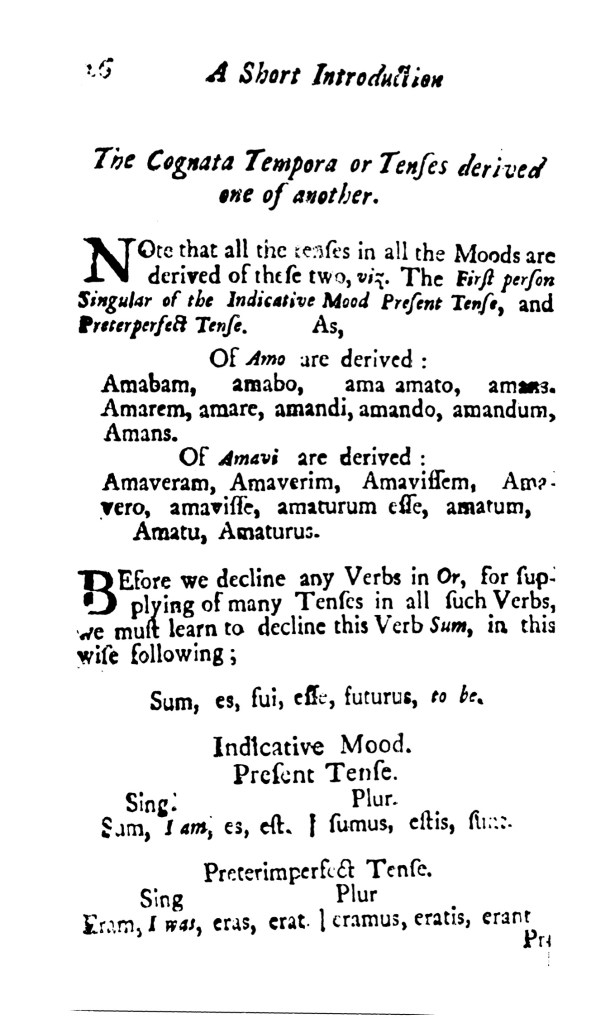

In early 16th century England, a Latin grammar in English was produced attributed to William Lily. Henry VIII made it the sole Latin grammar for use in schools. In one form or another, it would remain the main textbook for Latin in the English speaking world for centuries. It was so widely used that Shakespeare would allude to it in several plays and quote it in Henry IV, Part 1, when the thieves’ setter Gadshill says, “Homo is a common name to all men” (Act 2, scene 1).

The first pages of the 1544 edition of Lily’s An Introduction of the Eyght Partes of Speche, with a preface by Henry VIII. See if you can find the line quoted by Shakespeare:

Meanwhile, William Camden’s Institutio Graecae grammatices compendiaria in usum regiae scholae Westmonasteriensis, first published in 1595, would become the standard Greek textbook in the English-speaking world. Here is a sample from the 1833 edition:

Colonial New England

The focus of our story now shifts from Europe to North America, where Puritans from England fled to practice their rigid version of Christianity freely. Believing that it was evil to be uneducated, the colony of Massachusetts Bay enacted a series of laws in 1642, 1647, and 1648 mandating government-run public education. The aim was to produce students who would go on to college at Harvard and become ministers, lawyers, and perhaps doctors.

The second of these laws, known as the Old Deluder Satan Law, begins:

| It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of the Scriptures, as in former times by keeping them in an unknown tongue, so in these later times by perswading from the use of Tongues, that so at least the true sense and meaning of the Originall might be clowded with false glosses of Saint-seeming-deceivers… |

It should be no wonder, then, that the purpose of education in Puritan New England was to learn Latin, Greek, and Hebrew in order to read Scripture.

Many Puritans also appreciated classical authors and read them in addition to the Bible. The thought was that “the pagans” of ancient Greece and Rome—or some of them—had ideas that could help elucidate Christian belief, even if they themselves weren’t quite there yet. And the art of rhetoric perfected by the likes of Cicero could be used to express Christian ideas persuasively (Cothran, 2011). These uses of classical literature were common among the Church Fathers, so this wasn’t terribly radical.

That said, not all Puritans welcomed classical texts so readily. The Collegiate School was founded in 1701 in Connecticut Colony because Harvard had supposedly become too liberal. The school was renamed Yale in 1718. It was only after his appointment to professor of Hebrew, Greek, and Latin at Yale in 1805 that James Luce Kingsley made the controversial move to add Homer to the Greek curriculum beside the New Testament, but only on Mondays (Kelley, 1999: 134).

Bill Ziobro helpfully details the materials and methods of teaching Latin in colonial New England here and here. I rely on these pages for the rest of this section.

The standard elementary Latin textbook used in New England grammar schools until the mid-19th century was Ezekiel Cheever’s Accidence. Born in London in 1615, Cheever moved to America in 1637 and helped found Quinnipiac (later renamed New Haven Colony) before relocating to Boston. His book, first published after his death in 1708, was largely a compendium of Lily:

Cheever’s Accidence underwent twenty-three editions and was last published in 1838. That edition is available here.

Presumably Cheever’s instruction followed the method John Brinsley described in his 1612 The Posing of the Parts, a dialogue between teacher and student explaining the “accidence” (morphology) and “concord” (syntax) of Latin words. This image is from the 1638 edition:

Following Brinsley, a lesson might have proceeded like this:

| Q. How many sorts of Noune Substantives are there? A. Two: Proper and Common. Q. Which is a Noune Substantive Proper? A. Such is a Noune or name as is proper to the thing that is betokeneth, or signifieth: Or which belongeth but to one thing properly, as Edwardus Edward; so each man’s proper name. Q. What is a Noune Substantive Common? A. Every Noune which is common to more: or which is the common name of all things of that sort: as, homo, a man, is the common name to all men; so a house, or citie, or vertue. |

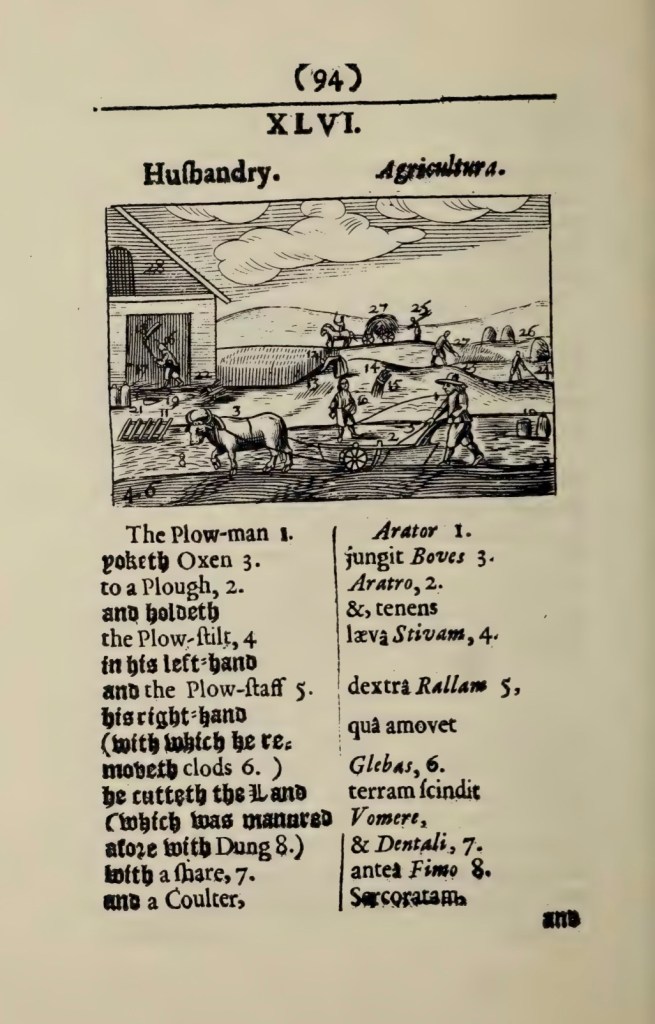

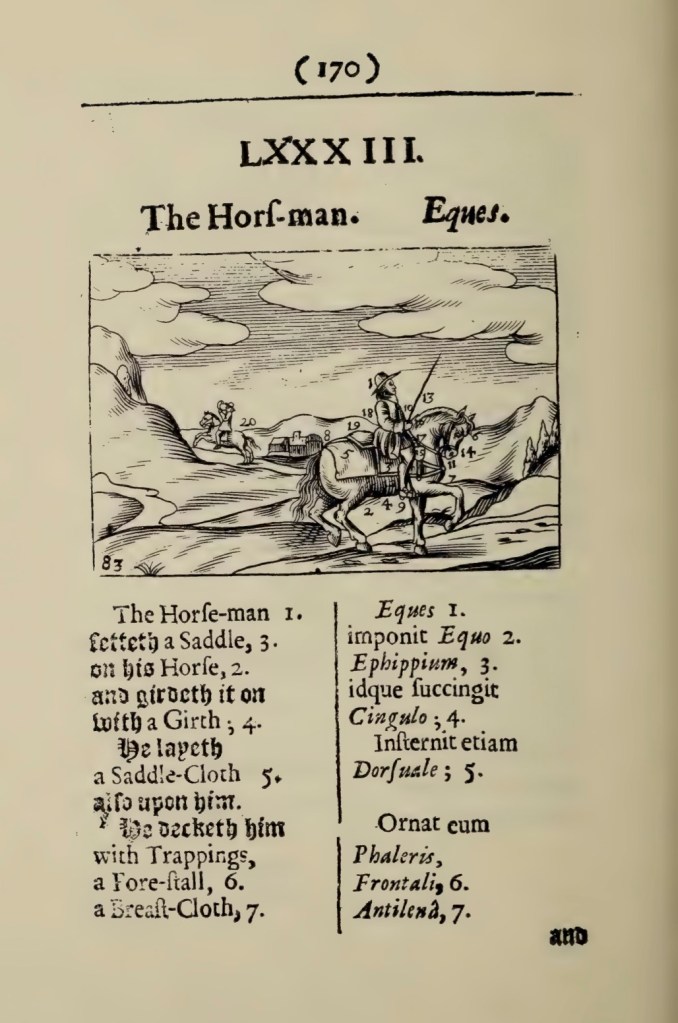

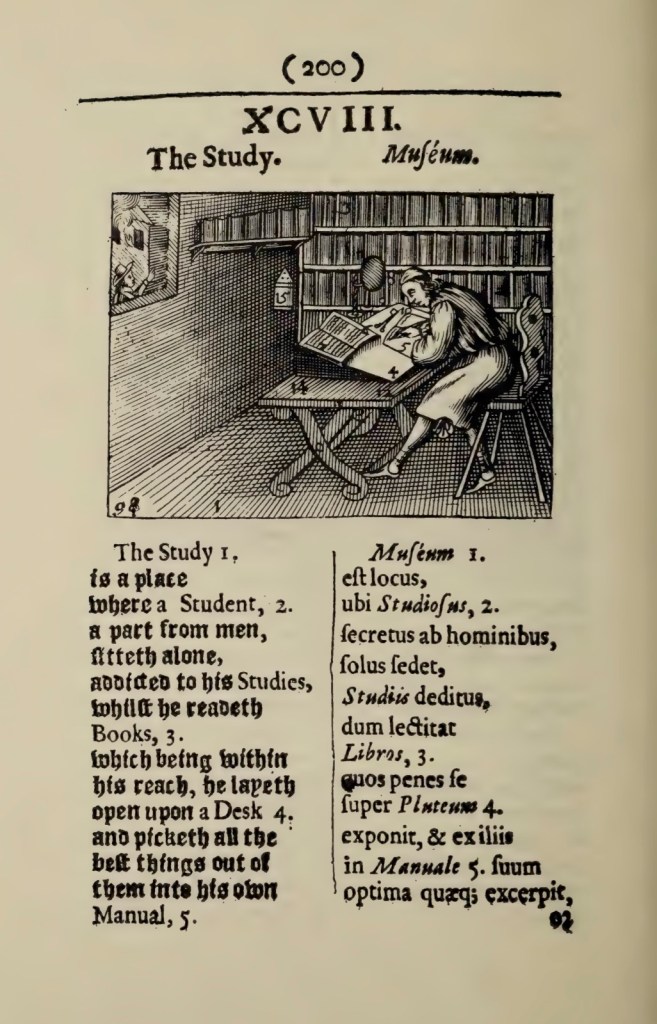

In their first year of study, students memorized definitions through extensive repetition. The second year was dedicated to building vocabulary. Books like John Amos Comenius’ Orbis Sensualium Pictus helped with this. First published in 1657 with an English translation by Charles Hoole in 1659, Comenius’ was one of the first children’s picture books. Its focus on both daily life and morality made it a particularly attractive school text:

Students spent the third year translating English into Latin. They also began translating Latin into English using easy texts like Aesop’s Fables, colloquia by Corderius and Erasmus, and Lily’s Carmen de moribus. From the fourth year on through college, students translated classical texts.

Requirements for entry to Harvard in 1642, similar to those of other colleges throughout the Colonial Period, attest to the importance of Greek and especially Latin in pre-collegiate education (Morison, 1935: 333, 433):

| When any schollar is able to read Tully or such like classicall Latine Authore ex tempore, & make and speake true Latin in verse and prose, suo (ut aiunt) Marte, and decline perfectly the paradigmes of Nounes and Verbes in the Greeke tongue, then may hee bee admitted into the Colledge, nor shall any claim admission before such qualifications. |

Once in college, lectures were often delivered in Latin and students were expected to converse in Latin. To be skilled in public speaking was important for the upper class. Students regularly participated in disputations and prepared declamations (Stray, 2007: 8-9). It was inevitable, then, that the curriculum emphasized classical rhetoric, especially Cicero and Quintilian.

The 19th Century

Much of the material we use today stems from, is a reaction to, or simply is what was published in the 19th century. Ethan Allen Andrews (1781-1858) produced America’s first great Latin dictionary, later revised by C. T. Lewis (1834-1904) and Charles Short (1821-1886) to become A Latin Dictionary, or for short “the Lewis and Short.” Around the same time in England, Henry George Liddell (1811-1898) and Robert Scott (1811-1887) produced a Greek-English dictionary, later revised by Henry Stuart Jones (1867-1939) to become A Greek-English Lexicon, or colloquially “the LSJ.” These remain the standard dictionaries in the English-speaking world.

The second half of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries saw a remarkable output of school texts and grammars by a generation of American scholars who studied philology in Germany. Names include Joseph Henry Allen (1820-1898), Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve (1831-1924), William Watson Goodwin (1831-1912), James Bradstreet Greenough (1833-1901), Herbert Weir Smyth (1857-1937), and Charles Edwin Bennett (1858-1921). Of these, all but Gildersleeve and Smyth were from New England. The latter was born in Delaware, the former South Carolina. Lest we think that Classics was just a New England thing, which it certainly was not (see for instance Jensen, 2018: 709-712), Gildersleeve fought for the Confederacy. With a permanent limp from a wound he received in the war, he likened himself to “the lame Spartan schoolmaster Tyrtaeus” (Briggs).

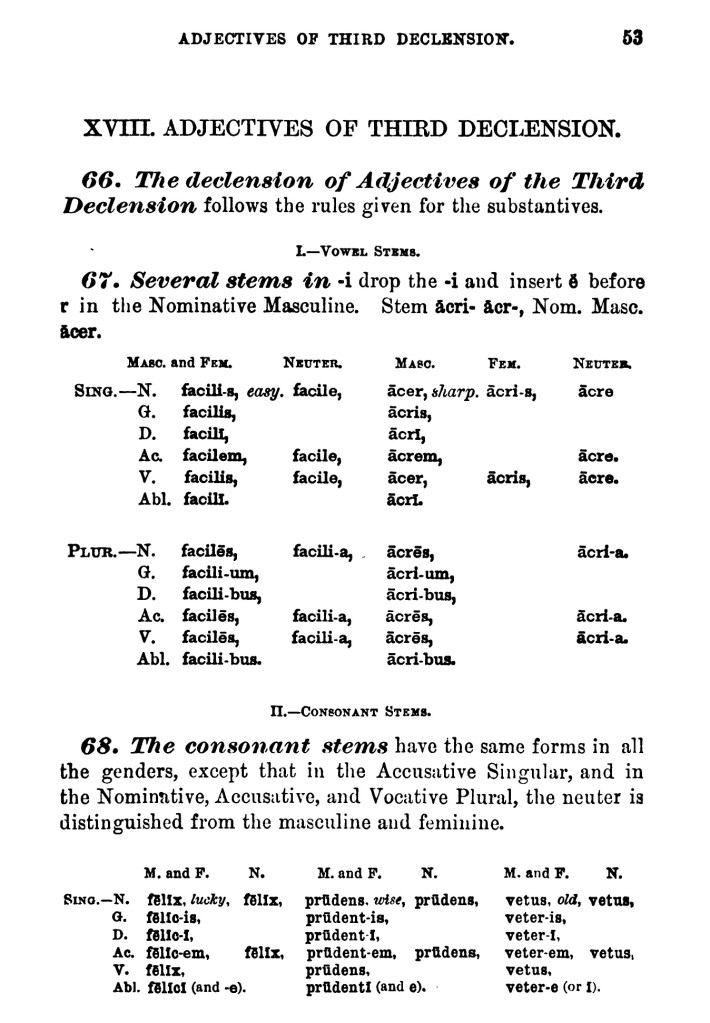

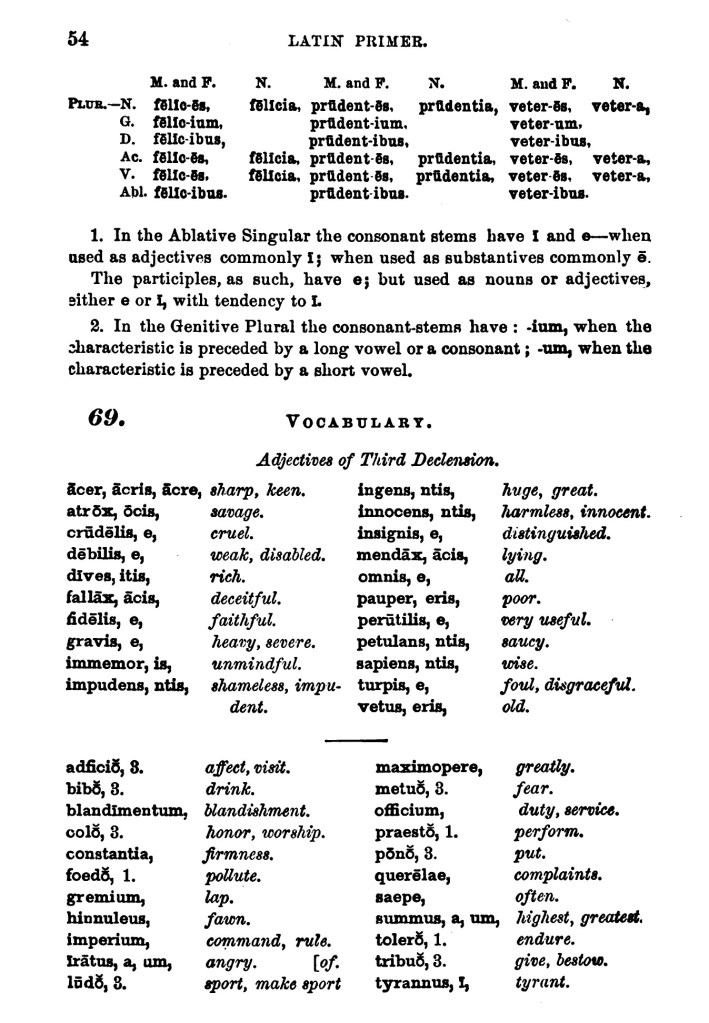

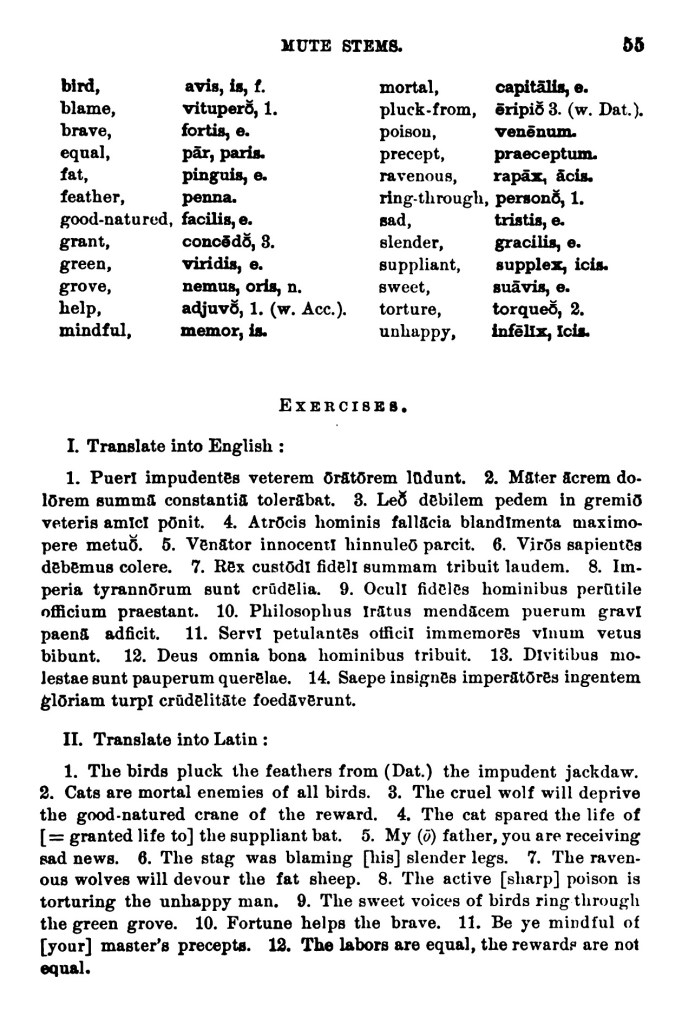

Numerous versions of an elementary textbook, First Lessons in Latin, were produced to accompany grammars by the aforementioned authors. See among others the 40th edition of Andrews’ version here, published in 1864, and Elisha Jones’ version here, published in 1882. Directing students to sections in those grammars for full content, they provided some supplementary grammatical material along with translation exercises in short two- or three-page lessons per topic. Once that grammatical material was written to work without reference to a grammar, thus producing a stand-alone textbook, the so-called grammar-translation approach was born. Gildersleeve’s own Latin Primer (1879) provides a good early example:

The grammar-translation approach may be characterized as follows. A chapter (or unit or lesson) covers an entire grammatical category: all cases and numbers of the first declension, or the whole perfect passive system, for example. The chapter begins with a discussion of the grammar with charts, where applicable. The detail of this discussion depends on pedagogical predilections and assumptions about the audience. Following this are sentences for students to translate, both from Latin to English and from English to Latin, targeting the grammar introduced in that chapter. There is also a short list of new vocabulary.

Curricular changes in the 19th century reveal a shift in emphasis from speaking Latin to analyzing written Latin. The goal of reading classical texts in the original remained unchanged since the Renaissance. However, increasingly one worked with Latin, as they had with Greek, as a subject to be examined more than a language with which one can engage actively. Notably, we start to find translation exercises written to test grammar but offering little in terms of content. Consider these sentences from the 1885 revised edition of Gildersleeve’s Latin Primer (62):

It is not hard to see how the study of Latin would soon seem out of touch.

The 20th Century until WWII

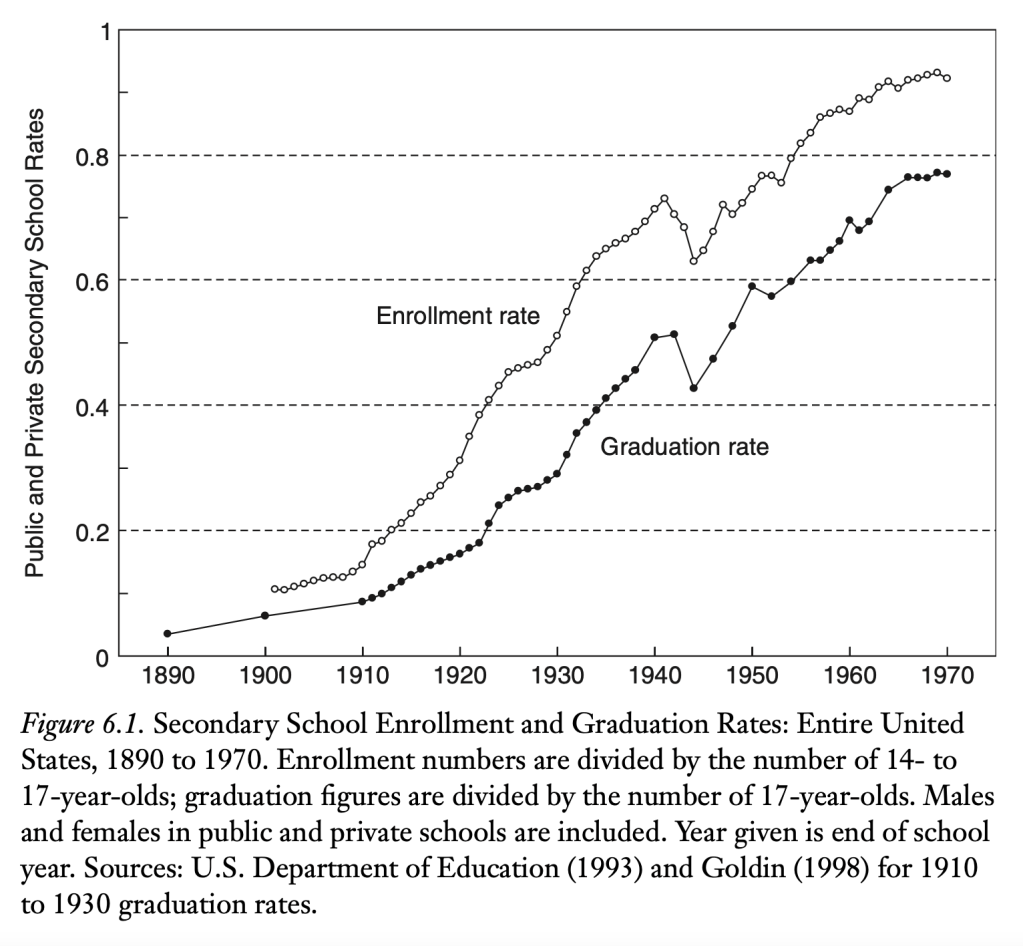

The 20th century saw a massive rise in high school and college enrollments in the U.S. They accompanied curricular shifts that impacted Greek and Latin profoundly. The so-called high school movement from 1910 to 1940, when it was disrupted by WWII, opened access to secondary education across the country. Now high school began to prepare students for jobs, not just college (Goldin & Katz, 2008: 198-199).

Figure 1: Public and Private High School

Enrollment and Graduation Rates in the US

Copied from Goldin & Katz (2008: 196).

The 18th and 19th centuries had already seen a shift in interest toward new scientific knowledge and modern languages and literature. Greek and Latin seemed less useful and their instruction increasingly boring (Ganss, 1954: 215-219; Stray, 2007: 5-6, 10). For Elisha Jones, the main purpose of the first year of Latin study was to acquire morphology and build vocabulary (1882: iv). Until the 20th century, learning Latin meant learning grammar rigorously and translating English into Latin and vice versa to solidify one’s command of Latin grammar. The goal was eventually to translate Cicero, Caesar, and Vergil from memory (Chickering, 1912: 34-35). There was a growing sense that at least the manner in which Latin was taught should undergo some change.

Frustrated with the current state of Latin pedagogy, W. H. D. Rouse, headmaster of the Perse School, Cambridge (UK) from 1902 to 1928, build a vibrant program on what he called the “direct method.” This approach to Greek and Latin, as well as French and German, emphasized oral communication in the target language (English was forbidden) and comprehension of the language without translation. It was, as Rouse himself claimed, “the right way to teach modern languages” (Rouse & Appleton, 1925: 1, emphasis mine). For a contemporary critique of the method, see John Kirtland (1913). “We may, indeed,” he concludes, “safely adopt all that goes with the direct method except its directness” (363).

According to the direct method, grammar should be acquired inductively through reading lots of easy Latin (Chickering, 1912: 37), where “easy Latin” seems to have meant full immersion in Neo-Latin. Consider the opening pages of R. B. Appleton and W. H. S. Jones’s Initium; a First Latin Course on the Direct Method, published in 1916, one of many direct method textbooks that appeared at the time:

To hear recordings of Rouse and his students practicing Latin, see here.

Despite some dedicated followers, Rouse’s direct method was short lived due to practitioners dying in WWI, lack of endorsement from the Classical Association in the UK and the American Classical League in the U.S., misogyny (many teachers were women), and an almost prohibitive degree of skill required to teach the method effectively (The American Classical League, 1924: 235; Stray, 2007: 9; Stray, 2011). Its legacy survives in the view that learning grammar is not learning a language, and students deserved more. Some continue to feel that Latin especially but perhaps also Greek should be taught like a modern language.

In the U.S., meanwhile, a 1924 report by the American Classical League called The Classical Investigation called for broad curricular shifts with new emphases on inductive grammar acquisition, inclusion of (actually) easy Greek and Latin, reference to Greek and Latin for improving one’s English, and the study of culture and history in English (Ullman, 1925; Honey, 1939: 38-39).

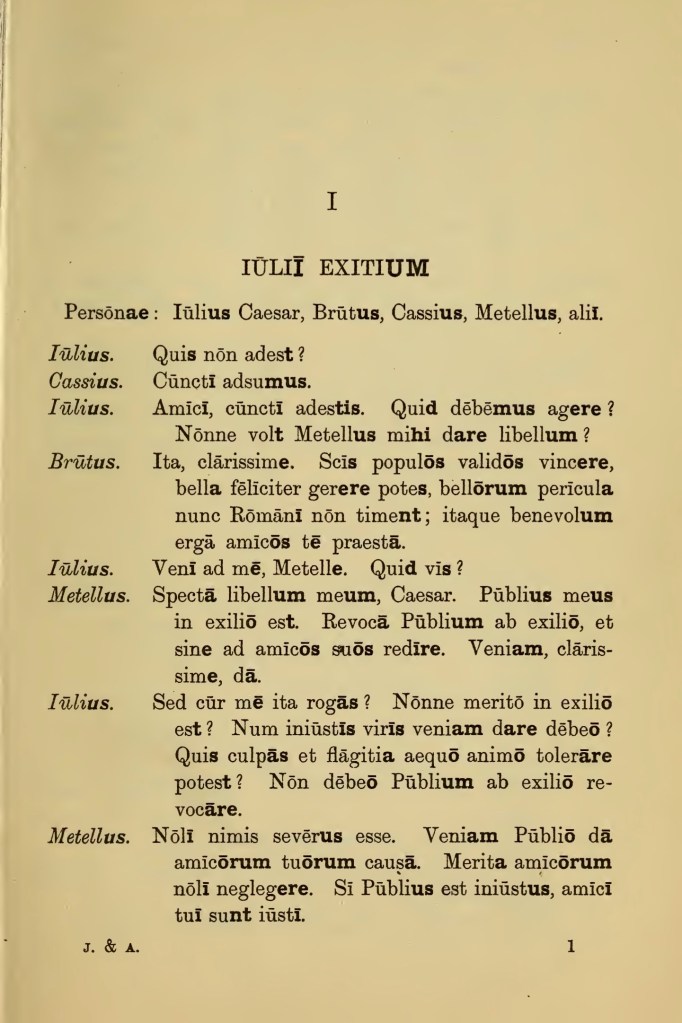

Beginning with Minnie L. Smith’s Latin Lessons, first published in 1913, teachers in the U.S. produced high school materials that would variously be revised, expanded, abridged, and combined over the decades to become the Jenney Latin series, the most popular grammar-translation approach textbooks for high school Latin in the 20th century (Castle, 2023). Here is Lesson X on the third declension from Smith’s original Latin Lessons (32-34):

In her preface Smith said her four aims were “to make the Latin language seem alive; to make the first year’s study of value for general culture; to minimize the difficulties of beginning Latin; to prepare thoroughly for the second year’s work” (iii). As a result, she and others who published in the series were instrumental to the survival of high school Latin in the U.S.

Taking to heart the American Classical League’s recommendations, Henry Lamar Crosby and John Nevin Schaeffer published An Introduction to Greek in 1928. Their preface begins (iii):

| “The glory that was Greece” means little to a student whose first Greek book presents only grammar. This Introduction to Greek gives him an insight into the brilliant achievements of ancient Greece, and at the same time, in a logical, thorough, and interesting manner, it develops in him the power to read Greek. |

To consider Lesson XLIV (145-148) for example, we find a quote from Diogenes, relatively basic grammar explanation, abundant exercise sentences, adapted Plutarch, a photograph of a Parthenon frieze, and at least one connection to English (“The suffix -σις, both in Greek and in English, denotes a name of an action,” 148):

The 20th Century after WWII

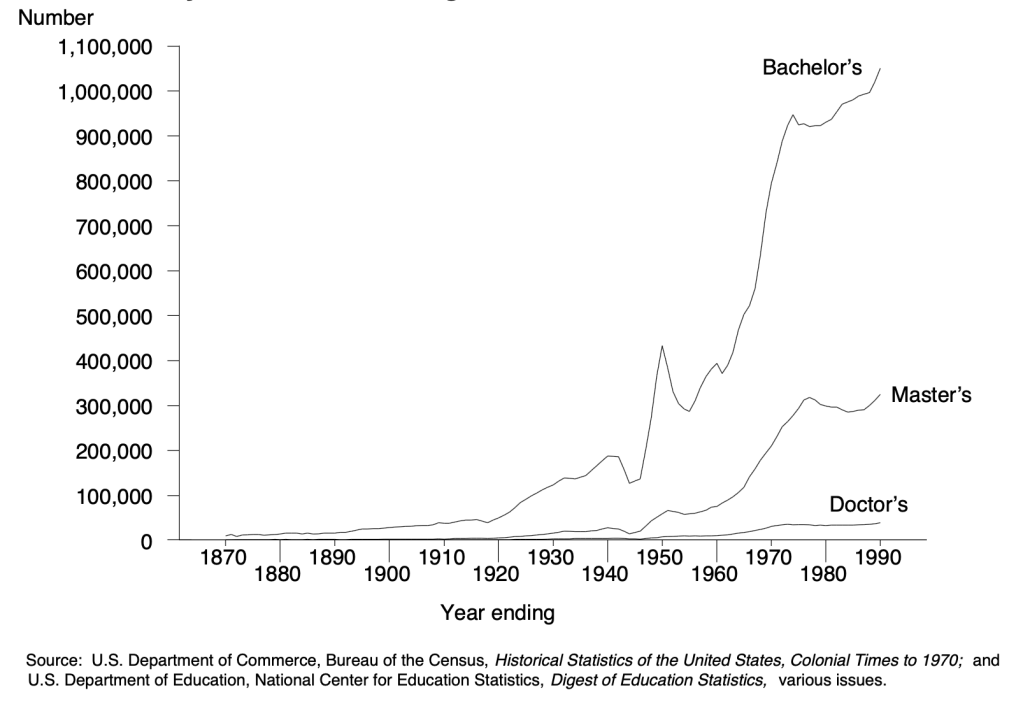

College enrollments in the U.S. surged after WWII. The G.I. Bill of 1944 helped veterans pay for college, which led to a spike in enrollments in the second half of the 1940s. Then, the 1960s saw unprecedented federal and state funding of higher education and growth of public university systems (Mintz, 2022). Furthermore, fear of the draft during the Vietnam War encouraged many to continue on to college, and stay there, who might not otherwise have done so.

Figure 2: Undergraduate and Graduate

Degrees Conferred from 1870 to 1990

Copied from U.S. Department of Education (1993: 67).

The various moves to make education accessible were tremendously important for society at large. At the same time, they were detrimental to Greek and Latin. The high school movement saw Latin demoted from a requirement to an elective. While the absolute number of students enrolled in Latin initially increased, the percentage of students taking Latin plummeted. Not long later, in the 1960s absolute enrollments plummeted as well.

Figure 3: Percentage of Public High School (and

Middle School from 1948-2007) Students Enrolled in Latin

Data from U.S. Department of Education (1993: 50) and Crane (2015: 5-6). Numbers from 1948 on are Crane’s and include middle school as well as high school. Columns are not equal chronological intervals.

Figure 4: Absolute Number of Public High School (and

Middle School for 2004 and 2007) Students Enrolled in Latin

Latin enrollments in public high schools from the U.S. Department of Education’s Digest of Education Statistics and Crane (2015: 5-6), whose numbers for 2004 and 2007 include middle school as well as high school. Numbers are in the thousands. Columns are not equal chronological intervals.

Overseas, in the UK the number of so-called comprehensive schools—secondary schools that accept students regardless of academic achievement, like public schools in the U.S.—grew significantly after 1965. Meanwhile, Oxford and Cambridge removed a classical language as a requirement for entry. Elsewhere, the Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican of 1963, commonly known as Vatican II, permitted the use of vernacular in liturgy. Thus began a shift away from Latin even in the Catholic world.

The teaching of Greek and Latin faced a series of agonizing reappraisals throughout the 20th century in both the U.S. and the UK. It was no longer self-evident that one should learn the languages once they ceased to be compulsory. Indeed, the historical elitism associated with them could be as much a deterrent as an appeal. Teachers could argue, as they frequently did, that taking high school Latin would improve one’s SAT scores. How effective an argument this was for enrollments I don’t know. One way or another, teachers needed to think of new ways to draw students to the Greek and Latin classroom.

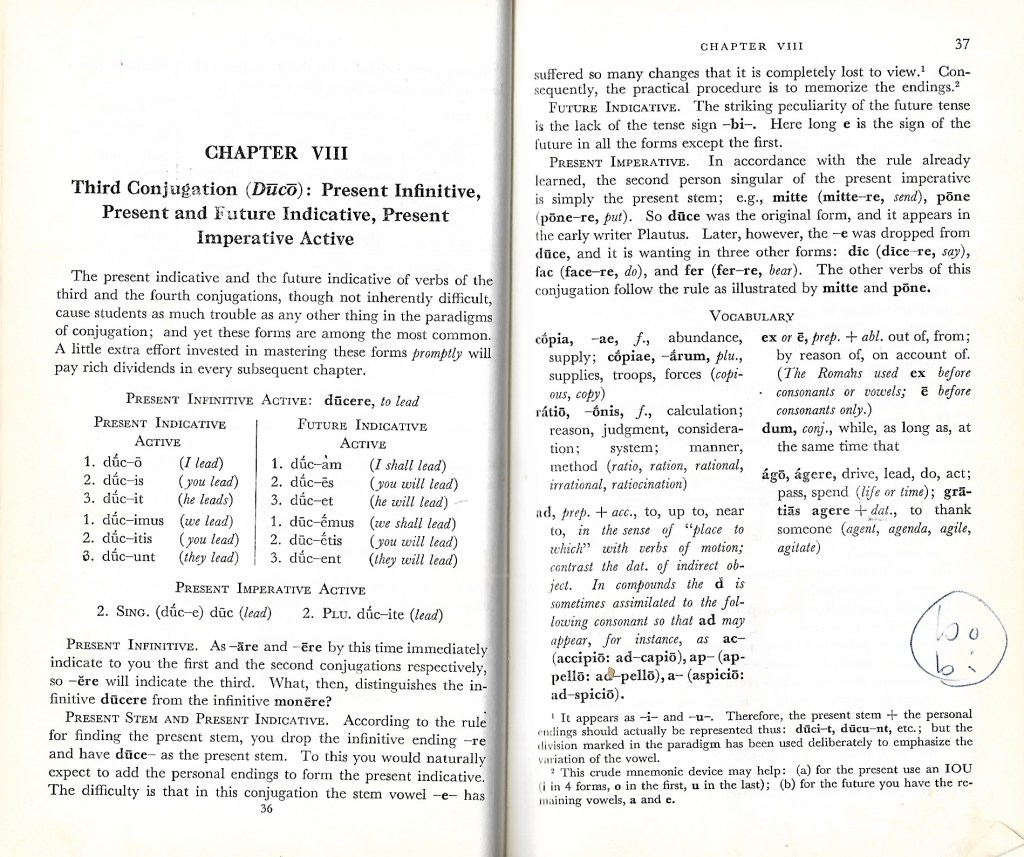

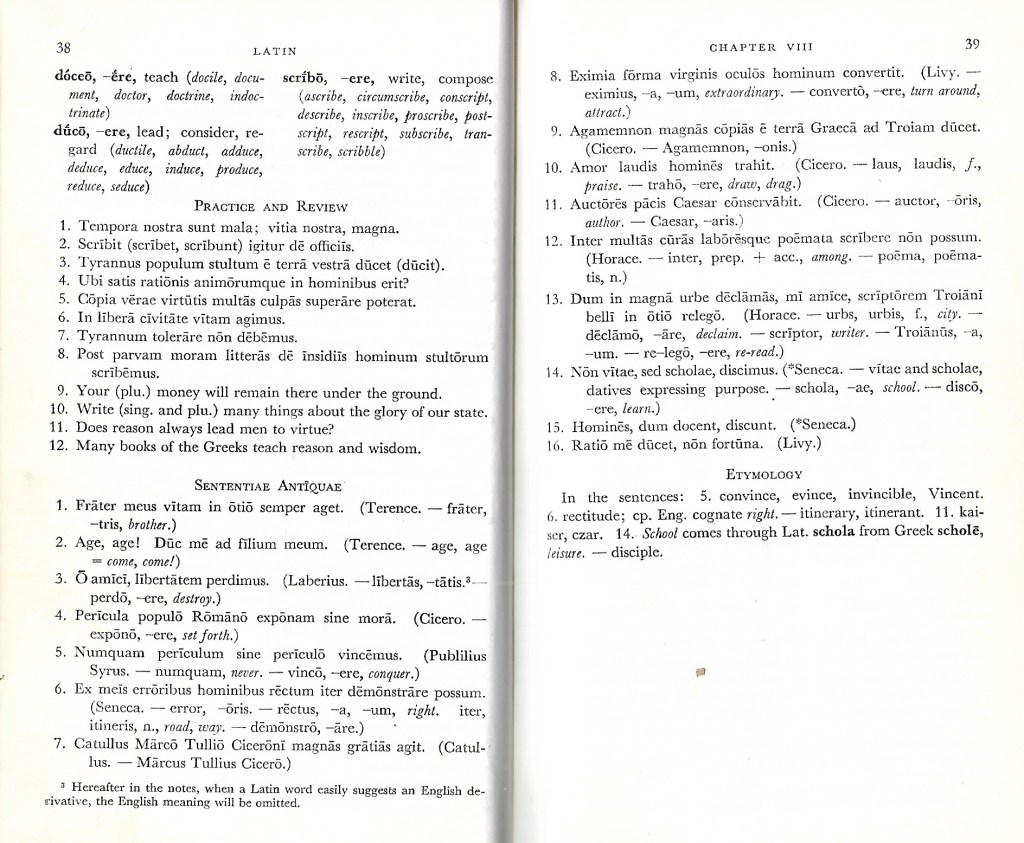

To backtrack momentarily, the 1950s saw the publication of two foundational modern Latin textbooks: Hans Ørberg’s Lingua Latina Secundum Naturae Rationem Explicata in 1955, later renamed Lingua Latina per se illustrata, and Frederic Wheelock’s Latin: An Introductory Course for College Students Based on Ancient Authors in 1956, known since 1995 as Wheelock’s Latin. The two books could hardly be more different.

Wheelock wrote his textbook primarily for college students with no prior experience with Latin and who might only have one year to study the language. He wished to give them something accessible but sufficiently rigorous that they could encounter authentic texts in their first year of study (Wheelock, 1956: vii-viii). The result was 40 chapters of concise grammatical lessons followed by exercise sentences to test the grammar in question and some sentences from ancient authors. After seven revisions, Wheelock’s Latin remains the most popular Latin textbook from the grammar-translation approach on the market, at least at the college level.

Chapter VIII, covering the third conjugation, from the 1st edition of Wheelock’s Latin:

For the ancient sentences Wheelock tended to select short statements of philosophical or intellectual value. “Caesar’s works,” Wheelock said, “were studiously avoided because there is a growing opinion that Caesar’s military tyranny over the first two years is infectious, intolerable, and deleterious to the cause, and that more desirable reading material can be found” (1956, viii n.2). One should read this statement both as a critique of Caesar’s traditional place in the Latin curriculum and as a reflection of Caesar’s reception in the U.S. after the defeat of Hitler and Mussolini.

Ørberg, by contrast, returned to the direct method—or a simpler version of it. The entire book is a narrative in Latin, with notes on vocabulary and grammar also in Latin. The narrative begins with the most intuitive of Latin, at least for a speaker of a Romance or Germanic language, and gets progressively harder, ever so slowly, until eventually one is reading adapted Caesar.

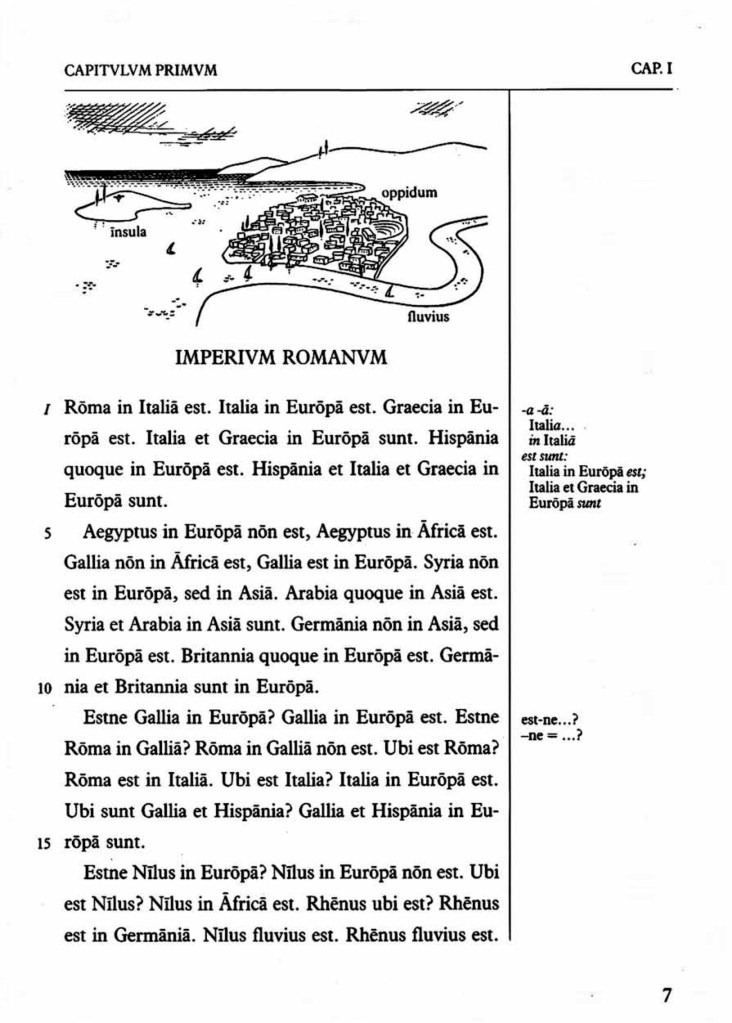

The opening pages of the 1991 edition of Lingua Latina per se illustrata, Pars I: Familia Romana:

While Lingua Latina itself might be too much for most—it is a slow process to which teacher and student alike must be dedicated—it inspired a new method called the “reading approach” that would be instrumental when the enrollment crisis of the 1960s arrived.

Unlike the grammar-translation approach, which prioritizes grammatical explanation and exercise sentences to practice that grammar, the focus of a book from the reading approach is a continuous narrative—a story—in the target language. Grammar is introduced piecemeal (the nominative in one chapter, the accusative in the next, for instance). The presentation of grammar, simplified as much as possible, is postponed until after reading to encourage inductive learning. Because the reading approach follows a story, history and culture come into focus. Short essays on cultural topics break up the narrative, and images abound that complement the essays and the narrative.

In response to the enrollment crisis of the 1960s, in 1970 and 1971 the Cambridge School Classics Project published five books of the Cambridge Latin Course (hereafter the CLC) in the UK. The first three books follow the life of a fictional Quintus, who survives the eruption of Vesuvius, travels to Alexandria, then relocates to Britain. The last two books concern the intrigues of a different aristocratic family in Rome.

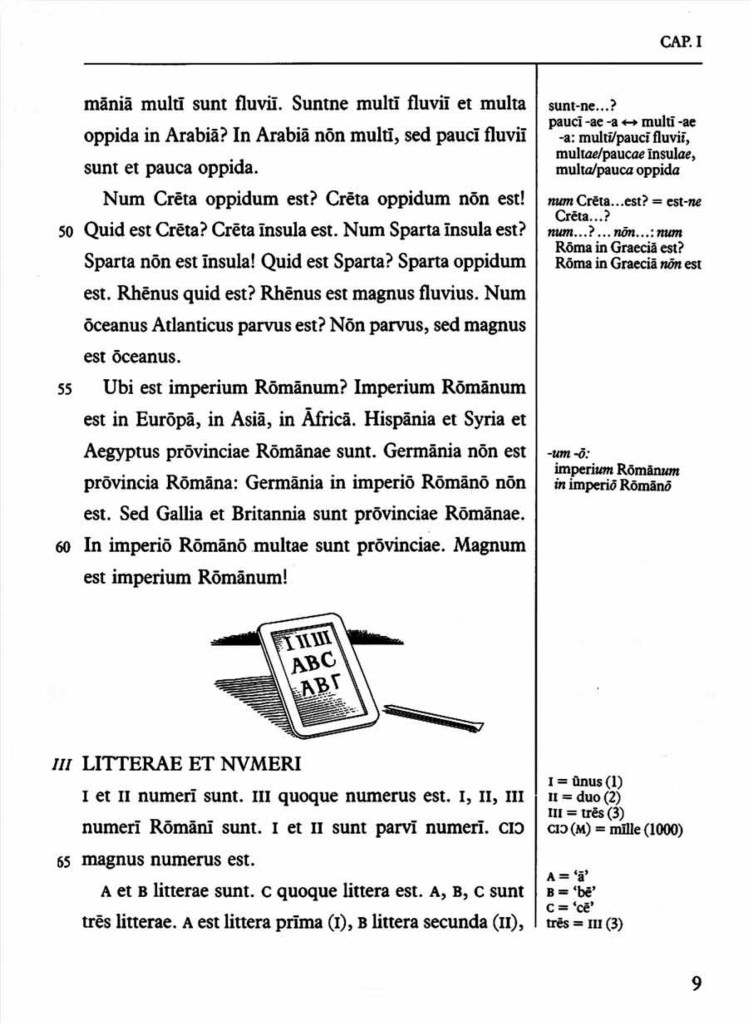

Here are pages from Unit 1, Stage 7 (2015, 5th edition):

The story made an indelible impact on at least some of those who read it. In the Doctor Who episode “The Fires of Pompeii” (Season 4, Episode 2), the Doctor—spoiler alert!—rescues Quintus’ family, who in the CLC died in the eruption of Vesuvius, and moves them to Rome.

For a while the CLC had competitors. In 1971, the Scottish Classics Group published Ecce Romani, whose main narrative concerned the events of a fictitious aristocratic family at Rome following the eruption of Vesuvius. In 2005, Pearson Education adopted Ecce Romani and abandoned Jenney’s First Year Latin, only to abandon Ecce, too, a few years later in 2009. In 1987, Maurice Balme and James Morwood published the Oxford Latin Course (hereafter the OLC) with a college edition for the U.S in 2012. Its story followed the life of Horace. But Ecce Romani and the OLC struggled to compete with the CLC, which remains by far the most popular reading approach textbook in high schools.

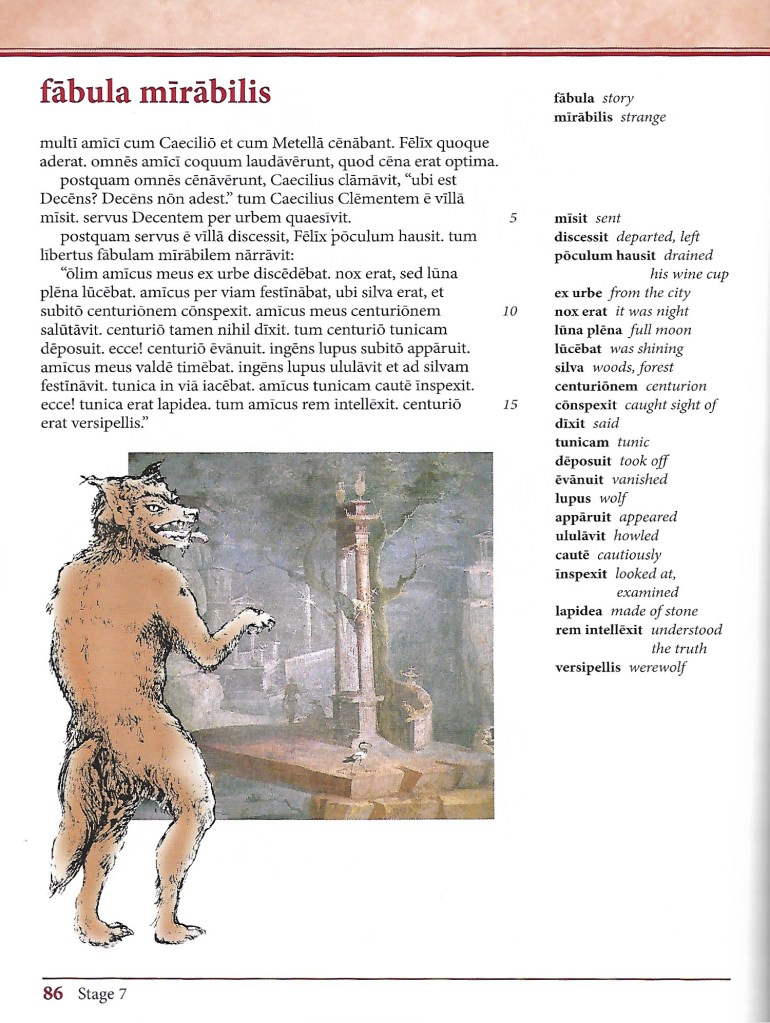

The opening pages of Ecce Romani (1990, revised combined edition) on the right and the OLC (1996, 2nd edition) on the left:

In short, toward the end of the 20th century and into the 21st, the situation with Latin was roughly this. In high schools, the standard textbook, Jenney’s, from the grammar-translation approach, was overtaken by books from the reading approach, especially the CLC but also Ecce Romani and the OLC.

Wheelock would come to dominate the college classroom. However, in 1977 Floyd L. Moreland and Rita M. Fleischer published their four-week intensive Latin materials used at UC Berkeley and CUNY as Latin: An Intensive Course. Perhaps less engaging than Wheelock but more efficient, Moreland & Fleischer was (and remains) available for advanced students who wanted to learn Latin even faster.

Of course, the reality was not quite this simple. In her 1990 survey of textbooks, Judith Sebesta counted no fewer than 66 distinct names of authors of beginning Latin textbooks. For Greek, that number was 24.

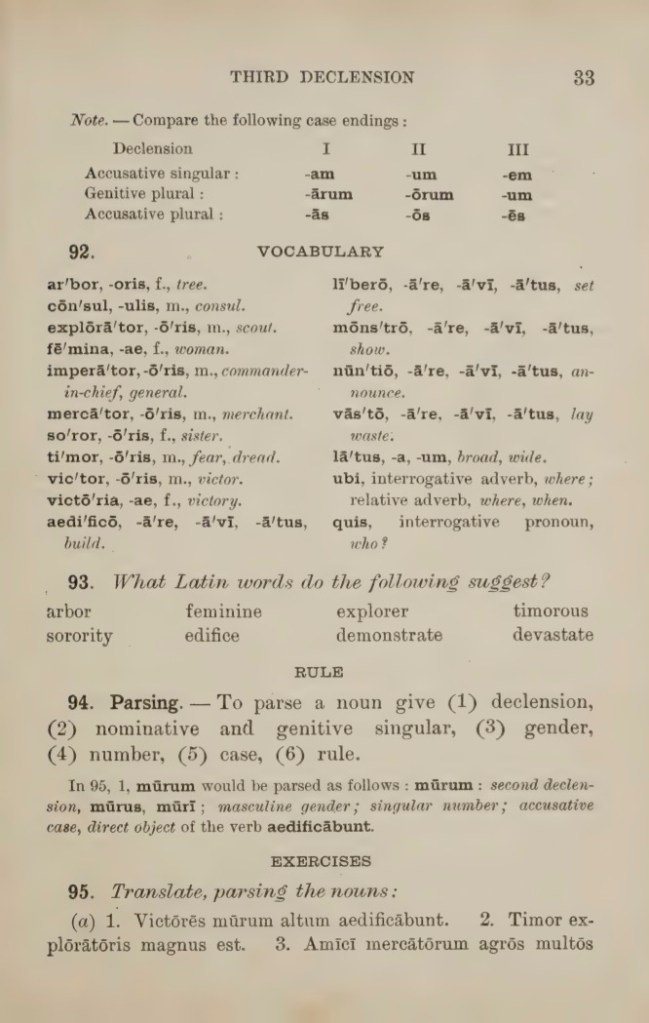

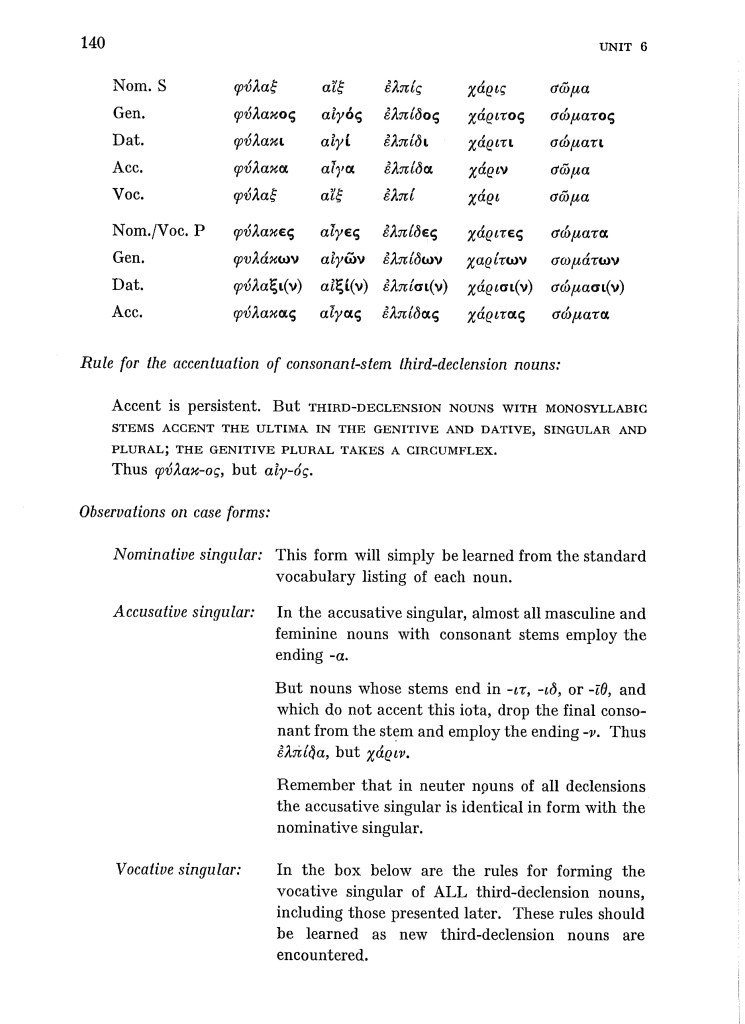

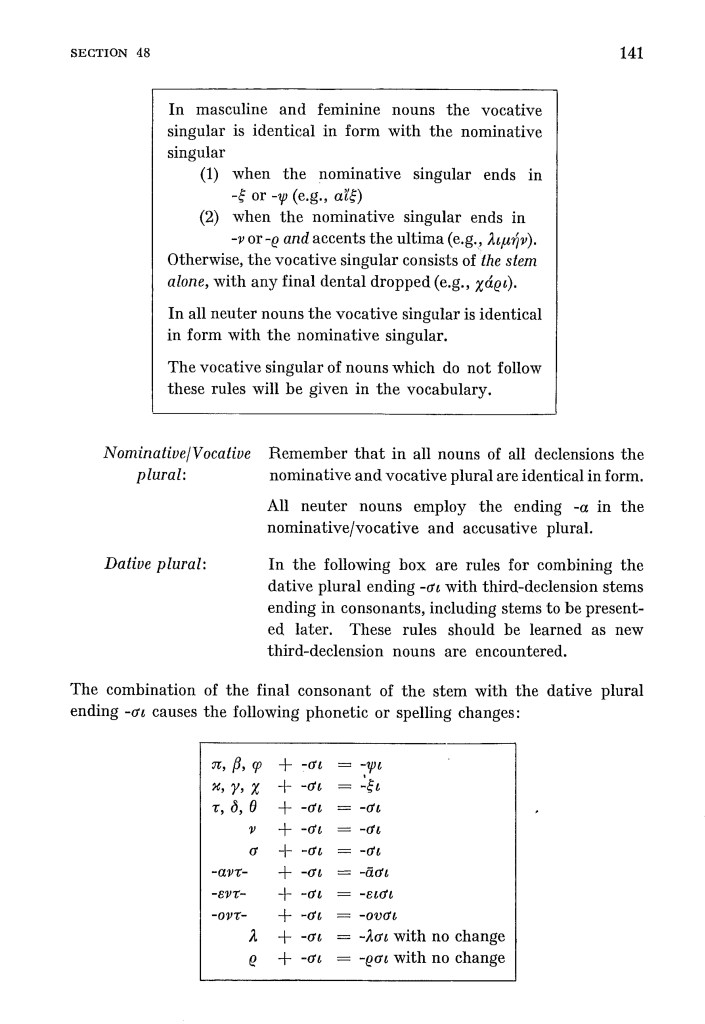

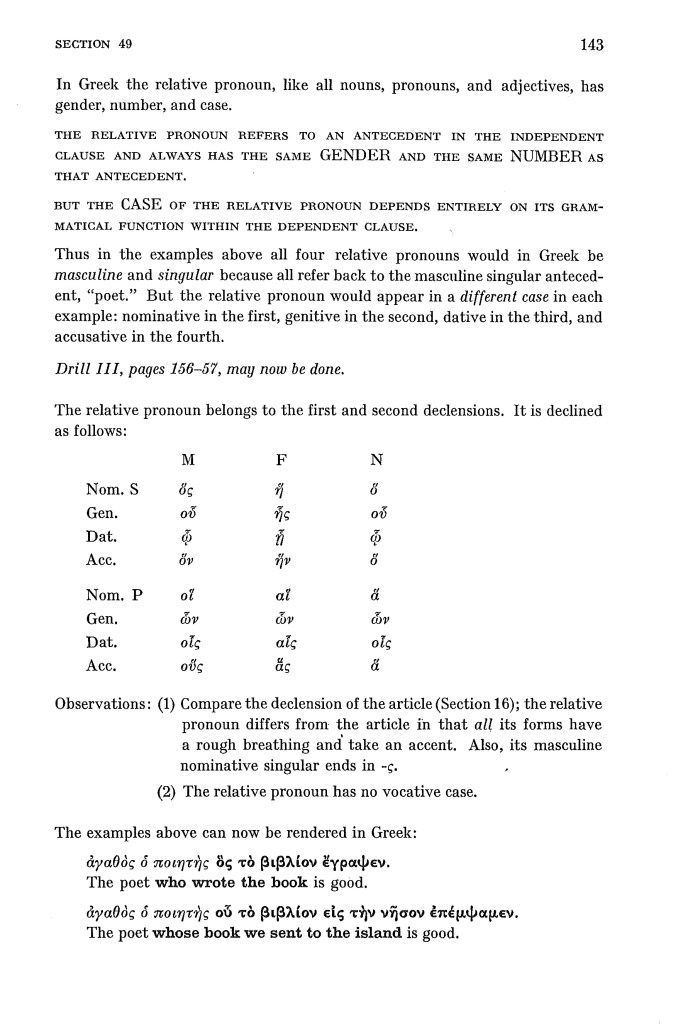

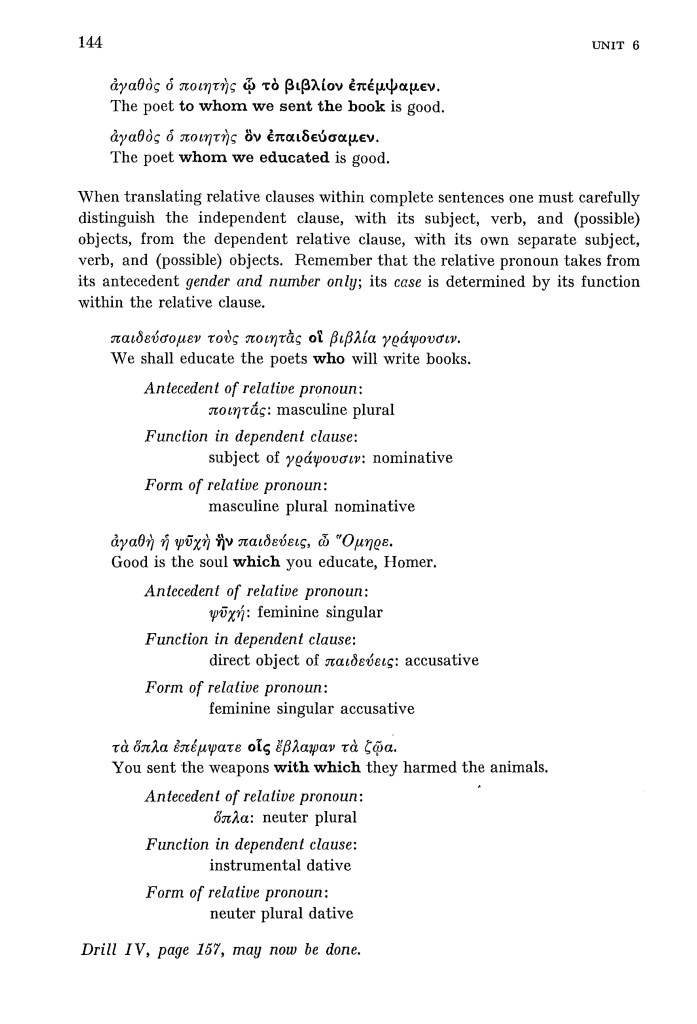

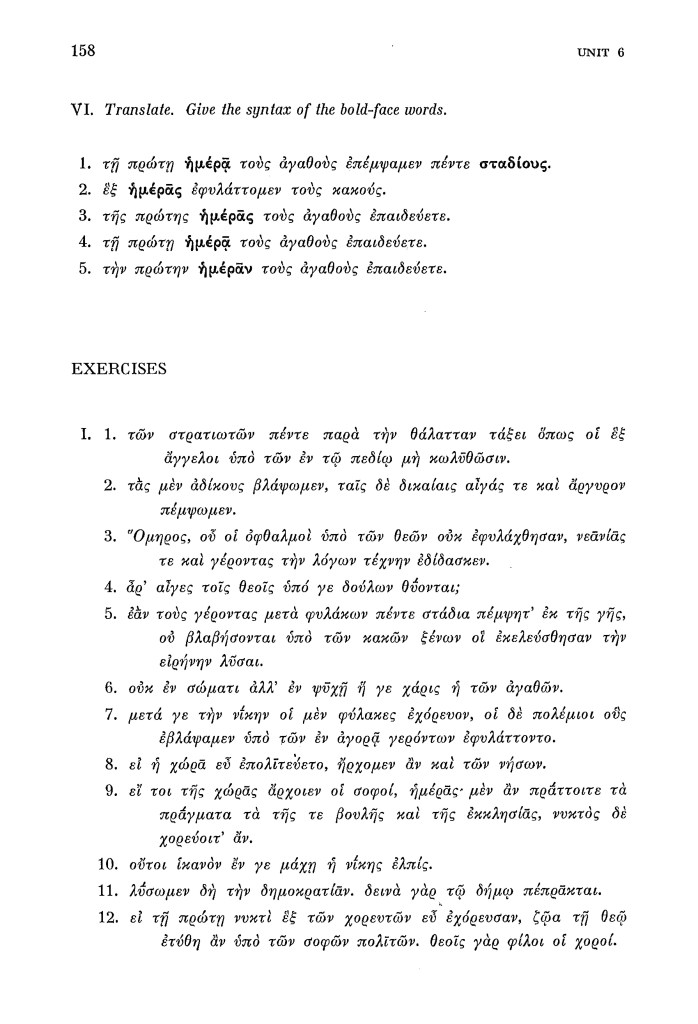

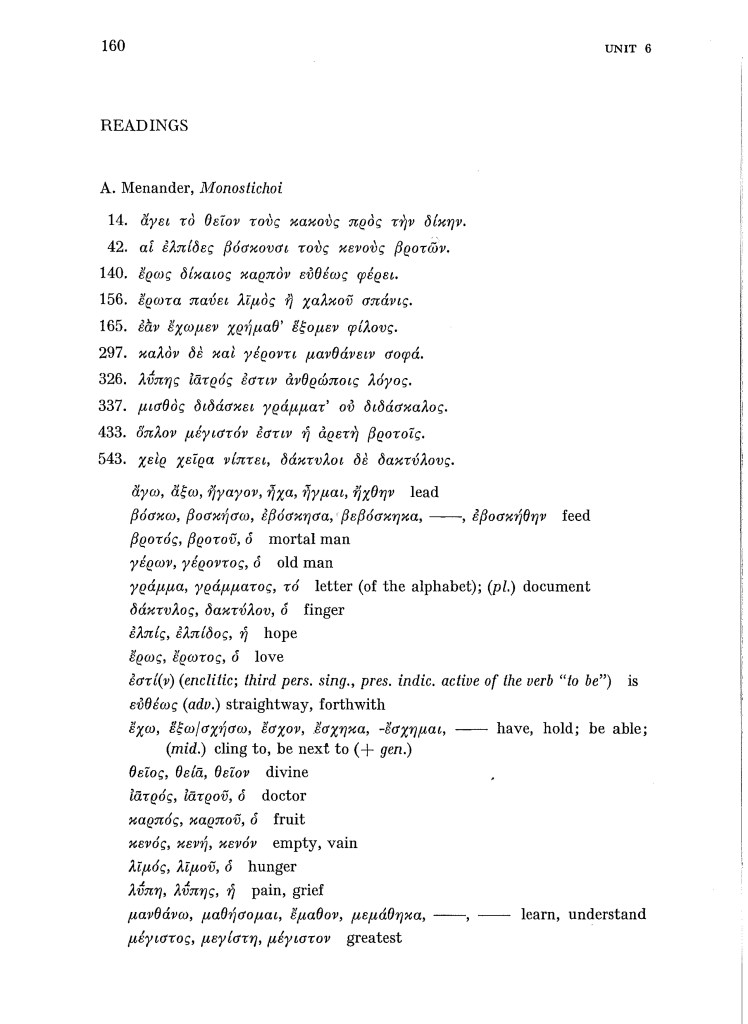

In 1980, Hardy Hansen and Gerald M. Quinn published Greek: An Intensive Course from materials they used in the Greek Institute of CUNY. See here for the 2nd revised edition, published in 1992. The authors acknowledged that Moreland & Fleischer’s Latin: An Intensive Course was their inspiration (vii), which they outdid in terms of intensity. Here are just nine of the 23 pages that make up Unit 6 (of 20 units total), covering third declension nouns, the relative pronoun, the independent subjunctive, and various uses of the genitive, dative, and accusative:

The textbook perhaps looks back to a time before the American Classical League’s The Classical Investigation when learning grammar, and lots of it, was considered a virtue. It remains widely popular in college classrooms, but inviting it is not.

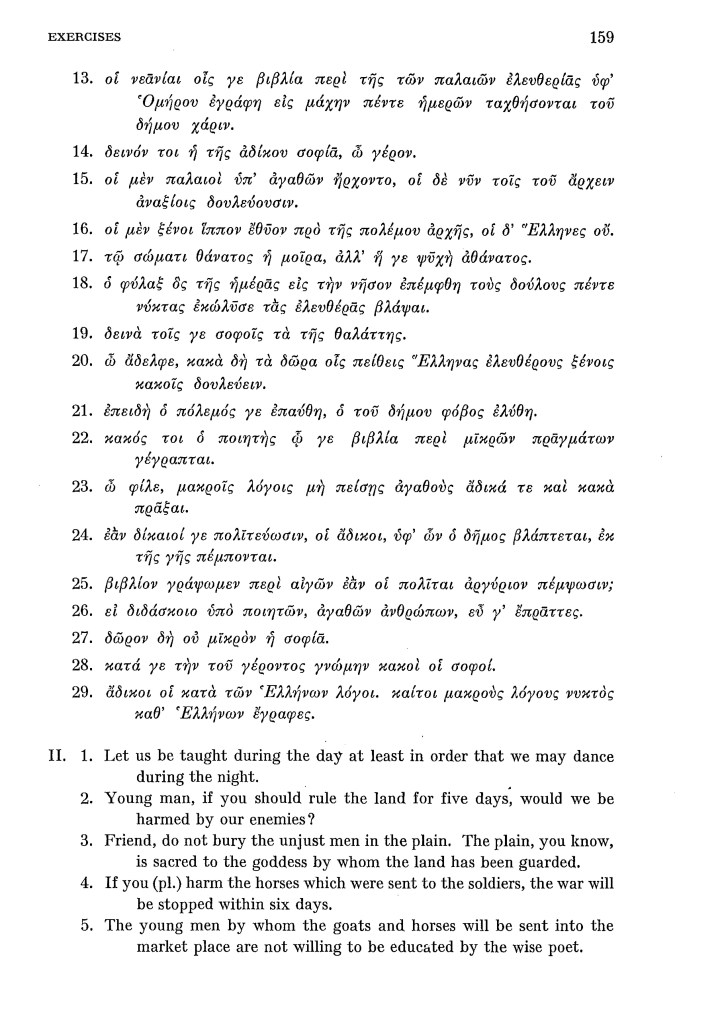

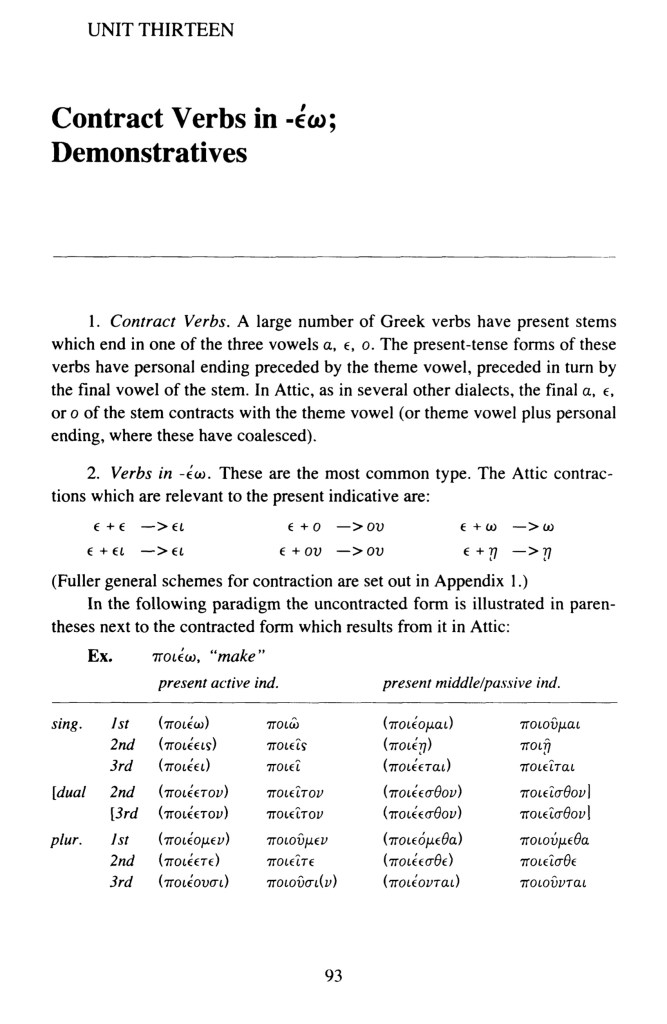

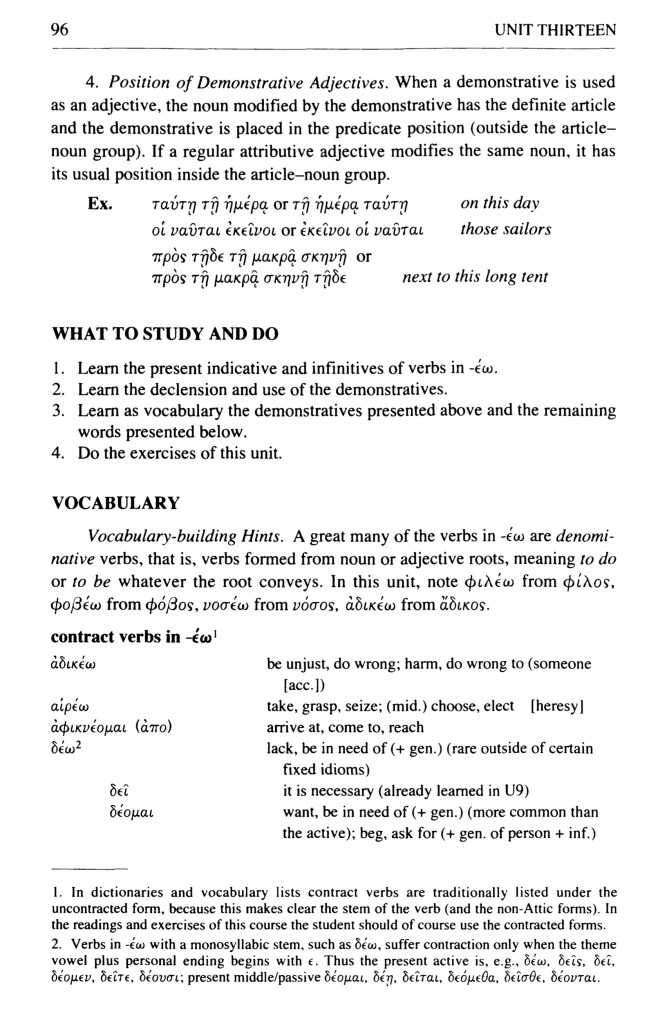

One year after the release of the 2nd revised edition of Hansen & Quinn, in 1993 Donald Mastronarde published Introduction to Attic Greek. In response to an unnamed standard textbook, he wished to give students full exposure to the grammar they would encounter in authentic texts without delay or assuming students would pick it up through osmosis (viii). Like Hansen & Quinn, the grammar is thorough, and little attention is paid to history or culture, but it works more naturally in a regular semester. Here is Unit Thirteen (of 42) of the 1st edition on -έω verbs and demonstratives:

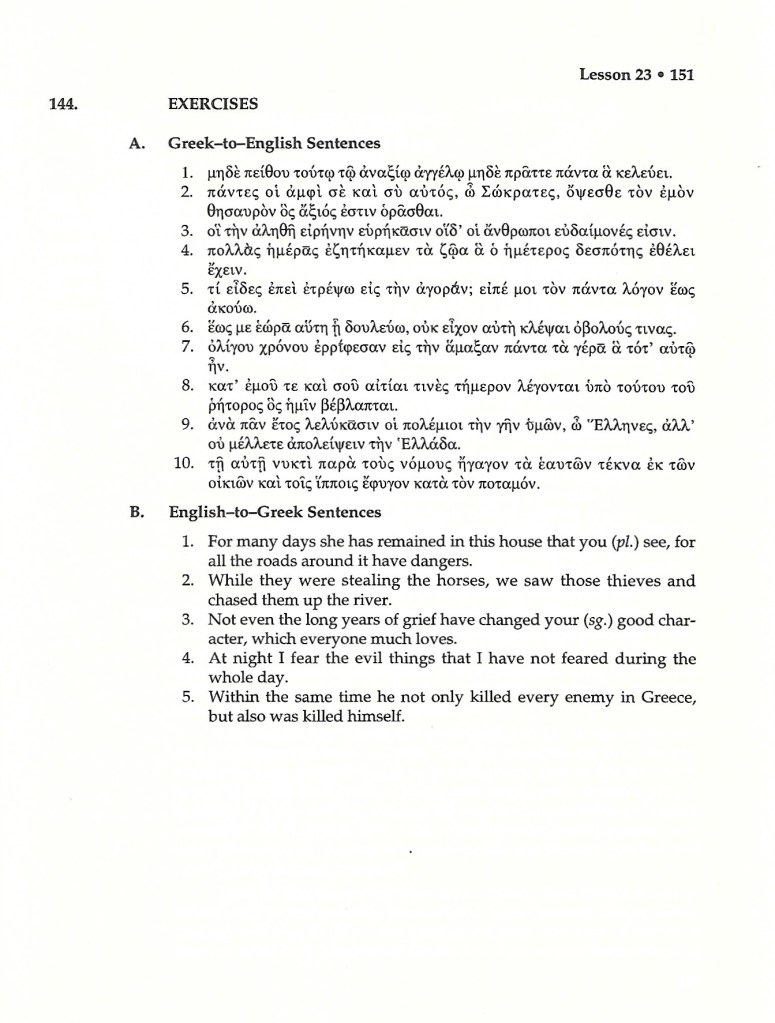

Then, in 1995 Anne Groton published From Alpha to Omega. Like Mastronarde, Groton designed her book for a standard college classroom—in her case, to be completed in a year at St. Olaf College. Here is Lesson 23 of the 1st edition on the relative pronoun, πᾶς, and expressions of time:

Eventually the reading approach also found its way into Greek pedagogy. In 1965, C. W. E. Peckett and A. R. Munday published Thrasymachus: A New Greek Course inspired by the direct method (see here for the revised 1970 edition). Like early Greek textbooks, it expected its students to have studied Latin and, following Rouse, threw readers into pretty complicated Greek quite literally from page 1:

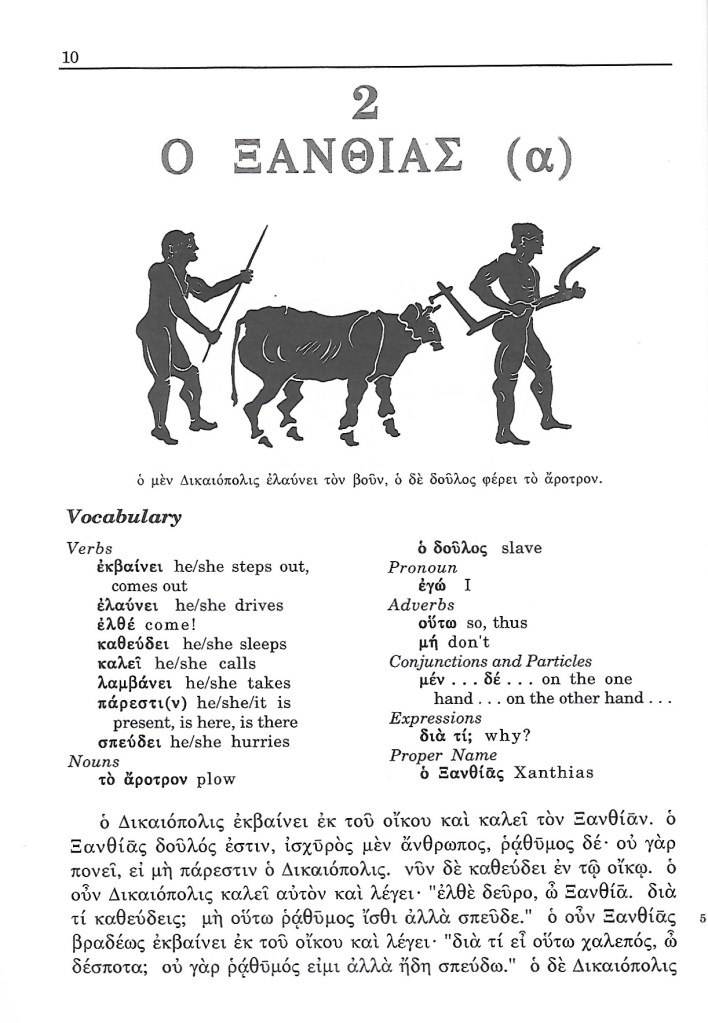

A more modest reading approach textbook came in the form of the Joint Association of Classical Teachers’ two volume Reading Greek in 1978 (for the 2007 2nd edition see here and here). But the exemplar of the reading approach to Greek was and surely remains Maurice Balme and Gilbert Lawall’s Athenaze, first published in 1990. Its story follows the fictional story of Dicaeopolis, the Athenian farmer from Aristophanes’ Acharnians, up to the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War.

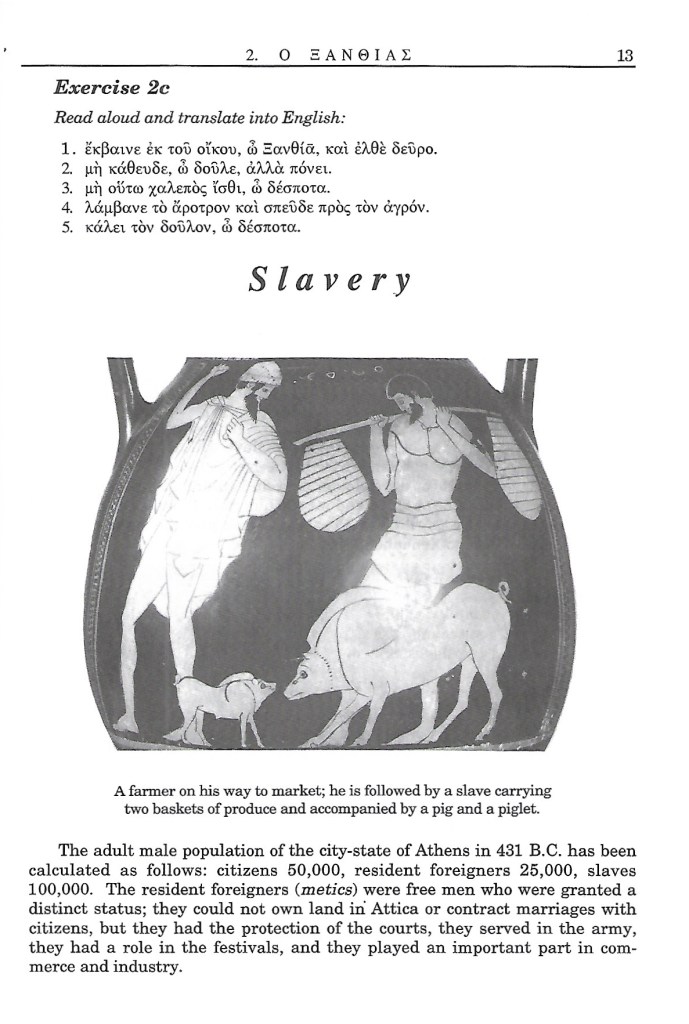

Here is the second chapter of Book 1 from the 1st edition, including a problematic discussion of ancient slavery to which I will return later:

Enthusiasts of the reading approach may find the Italian edition of Athenaze most impressive.

For reasons that will become clear in a moment, I would be remiss not to mention briefly the linguistics approach to Greek. Morphophonological patterns can be handy shortcuts that help make the seemingly endless number of charts a bit more manageable. In the late 1960s, Gareth Morgan developed an instructional method that taught students how to combine roots and morphemes to create final forms themselves. He self-published the material as Lexis in 1972 for use in the Intensive Summer Greek program at the University of Texas at Austin.

Morgan’s Lexis did not present a single paradigm of final forms—just the morphological tools, ever so simplified, to build them oneself. For instance, we find the totality of Morgan’s introduction to the strong aorist in the 1976 edition of his Lexis on the page to the left:

Morgan amassed a devoted bunch of initiates in his method of Greek instruction. They include the author of this post, James F. Patterson, who published the expanded version of Lexis in 2021. One challenge with the book is that it is a commitment, and many teachers will find the approach foreign. To increase the method’s accessibility, Patterson and David Welch are currently adapting the material so that it can accompany other textbooks.

The 21st Century

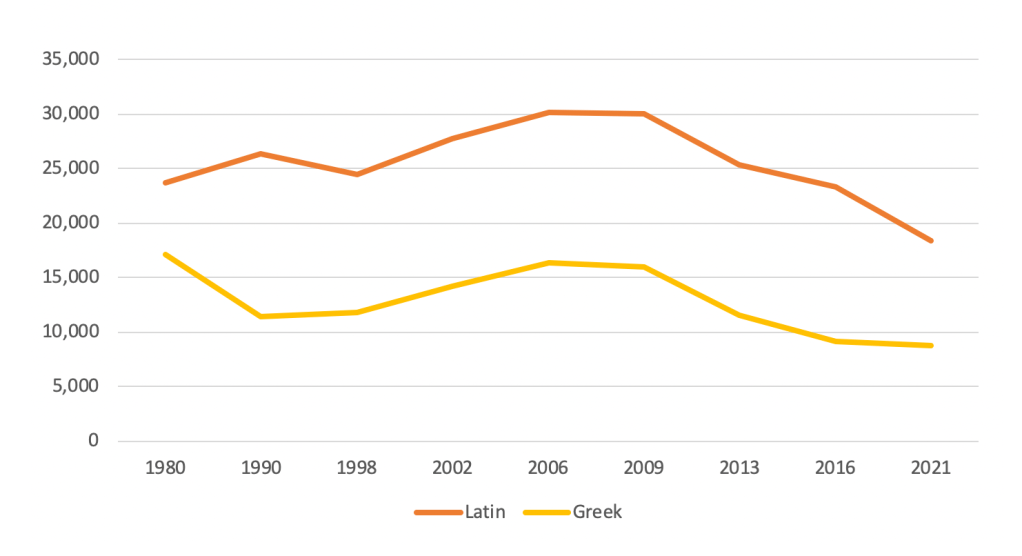

Greek and Latin enrollments have again fallen. The Great Recession of 2007-2009 shifted student priorities toward fields that promise more financial stability after graduation than the Liberal Arts traditionally have. Since then, the practical value of the Humanities generally and subjects like Greek and Latin specifically has been questioned even more than before.

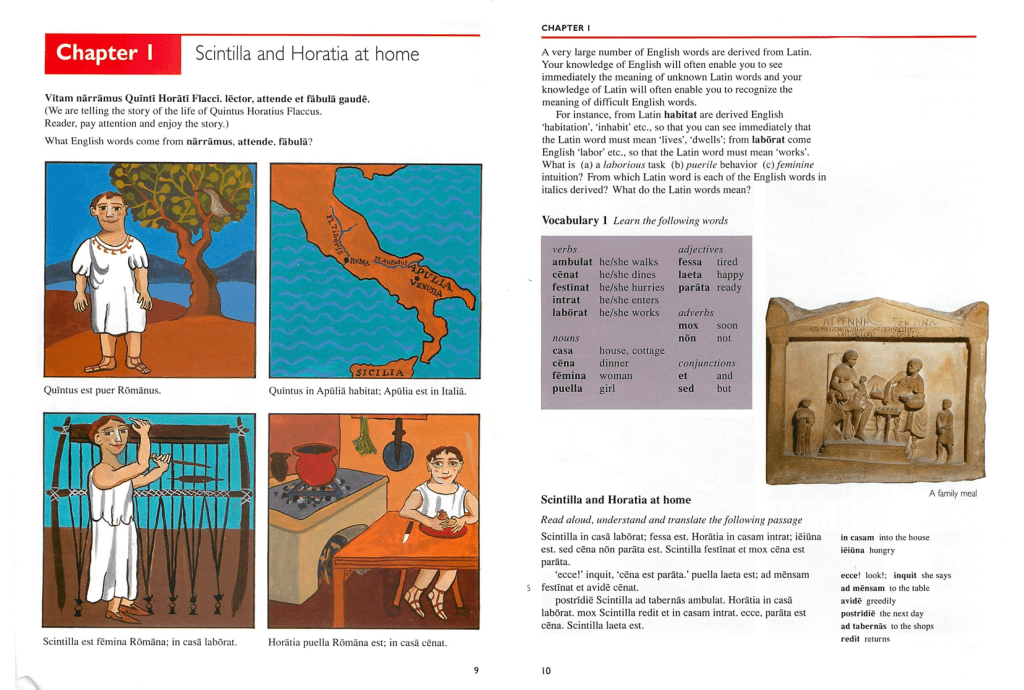

Figure 5: Undergraduate Enrollments in Greek and Latin

Data from Lusin et al. (2023: 53). “Greek” includes all premodern Greek and excludes the language when reported simply as “Greek” in case those numbers include Modern Greek. Years plotted are not at regular chronological intervals.

The various textbooks published in the past 25 years sometimes pick up where the 20th century left off or look back, knowingly or not, to earlier centuries in new ways. As always, socio-political circumstances help guide the conversation.

Andrew Keller and Stephanie Russell published Learn to Read Latin in 2004 and Learn to Read Greek in 2012. Inspired by the thoroughness of Moreland & Fleischer and Hansen & Quinn, they wanted textbooks that would introduce students to classical authors throughout their first year of study, not just at the end, hoping that students would continue beyond the first year of study when they see what sort of literature they can be reading. To do this, exercise sentences are thorough, and chapters conclude with heavily glossed authentic texts. Here is the end of Chapter 4:

Going further, in her 2018 Learn Latin from the Romans Eleanor Dickey found a way for even the exercise sentences—or some of them—to be authentic. Returning to the colloquia of classical antiquity she found in them both easy Latin and authentic classical Latin. After all, she notes in her preface, this material was written by genuine native speakers for students (xi):

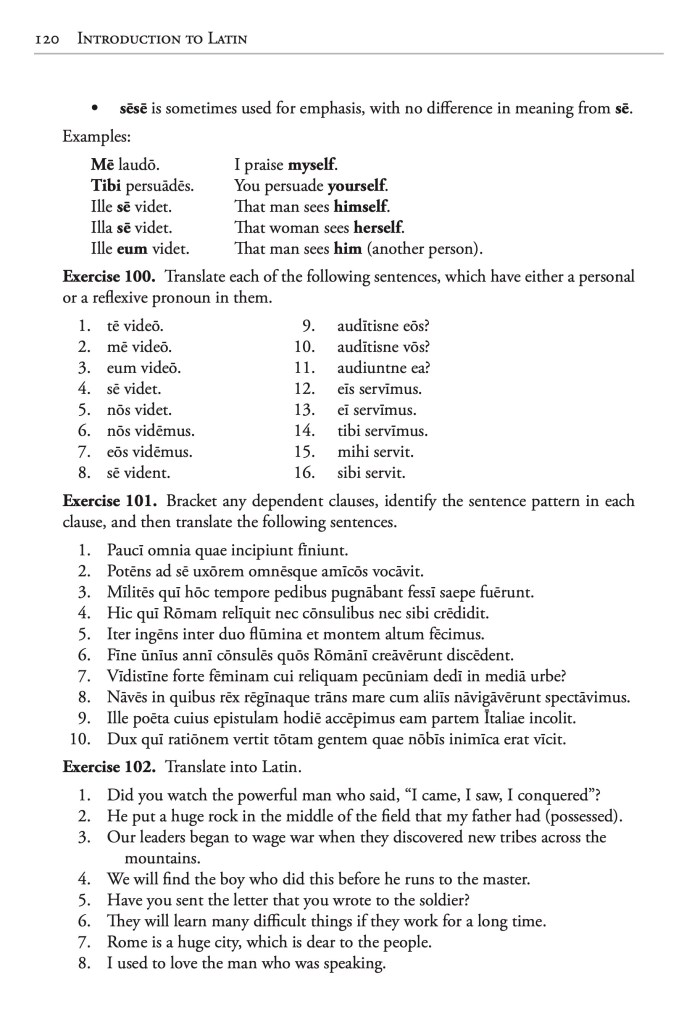

Taking a different approach, the Shelmerdine sisters separately published textbooks on Greek (by Cynthia, 1st edition in 2001) and Latin (by Susan, 1st edition in 2005) using a bare-bones grammar-translation approach with more types of exercises and extended readings than the standard textbook of the sort. Though still the underdog, Shelmerdine’s Introduction to Latin now competes with Wheelock’s Latin. Here is most of Chapter 13 on the relative and reflexive pronouns from the 2013 2nd edition:

In 2008 and 2009, Milena Minkova and Terence Tunberg published Latin for the New Millennium. Their idea was to produce a blended reading and grammar-translation approach with lots of extended passages and thorough grammar. Chapters also conclude with exercises for conversational Latin, making it an exemplum of mixed methods pedagogy. Notably, while the focus of the book is on classical Latin, the authors culled plenty of passages from Medieval, Renaissance, and early modern Latin texts as well. In so doing, they bring to life many Latin speaking worlds across time.

The sample pages below are from Level Two, Chapter 13, which begins with a lengthy passage from Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda’s 16th century De rebus Hispanorum gestis ad Novum Orbem Mexicumque, aka De orbe novo, and concludes with a conversation in Latin about diversity in the U.S.:

At some point teachers realized that the grammar-translation and reading approaches weren’t entirely different approaches after all. Rather, they stress different things and have different strengths and weaknesses. For instance, the reading approach is slow, sometimes infantilizing, and lacks the grammatical rigor students will need if the point is to read ancient texts. Meanwhile, the grammar-translation approach promotes passive learning, lacks good readings, and also struggles to prepare students to read authentic texts. Put another way, the two approaches aren’t distinct as much as they are perspectives that can supplement each other’s weaknesses. If we insist on binaries, it is the communicative approach that has (re)emerged as the rival.

In the 2010s, the Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements brought to the fore concerns about the role of Classics in various forms of social injustice over the centuries. Younger teachers especially began scrutinizing both the materials with and manner in which Greek and Latin have traditionally been taught.

As for materials, various textbooks including Athenaze, Latin for the New Millennium, Ecce Romani, and the CLC have been called out for offensive depictions and descriptions of slaves, women, and minorities (Robinson, 2017; Dugan, 2019). Observations of this sort were not new (see for instance Monat’s 1993 critique of Lingua Latina), but they became more public and taken more seriously. Some books have attempted to correct these issues in subsequent editions (Weale, 2022).

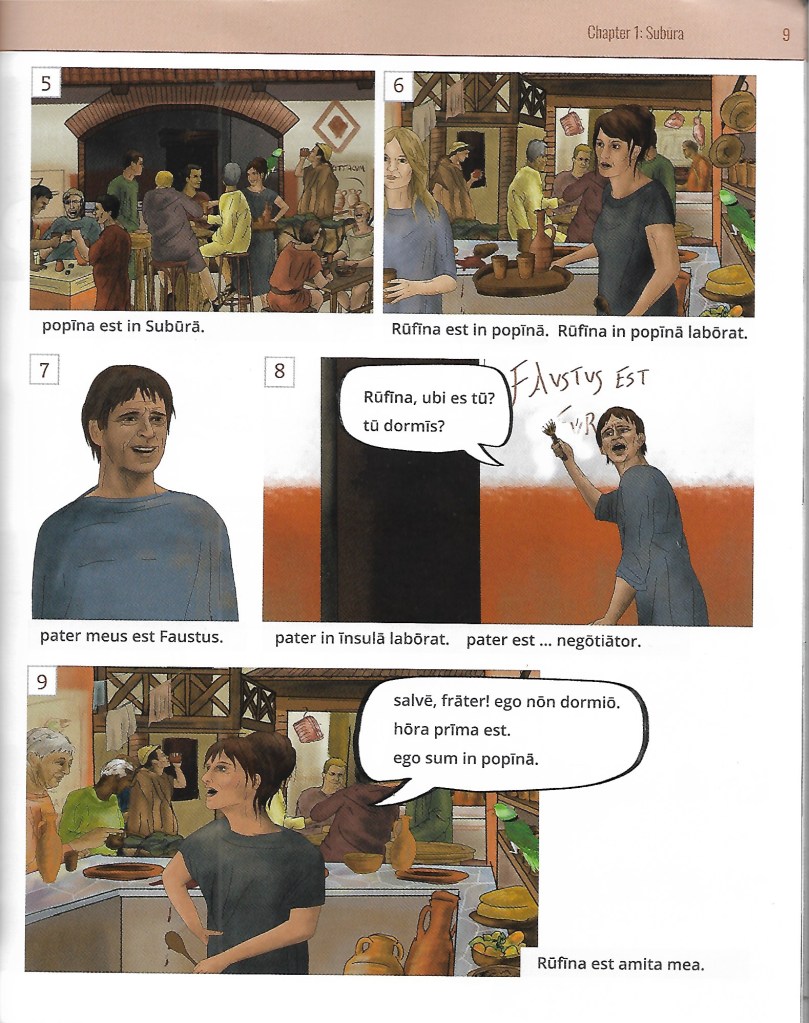

Meanwhile, in 2020 the first book of Suburani appeared. A reading approach with emphasis on dialogues partly in the form of a graphic novel, its intent was to emphasize the social diversity of the Roman world more realistically than other books on the market. Main characters include women, slaves, veterans, and the poor alongside the standard aristocrats, from different parts of the Empire.

As for the manner in which Latin is taught, there has been a revival in interest in teaching Latin like a modern language not seen since Rouse, though much more widespread now than it was then, at least in the U.S. A new generation of teachers has been inspired by the work of Stephen Krashen in the 1970s and 1980s. Krashen argued that people acquire another (modern) language when content in that language is presented to them just above their current level of understanding. This content is called comprehensible input. Though subsequent research says otherwise, Krashen thought that explicit language instruction did not facilitate language acquisition (Ellis, 2008: 356). Krashen’s view has appealed to instructors who find grammar instruction exclusive and ineffective.

Today, proponents of comprehensible input in Latin instruction are found throughout high schools and in some colleges. They differ in how and to what degree they employ Krashen’s theory, but listening and responding to spoken Latin is a centerpiece of the student experience in these classrooms.

Summer programs promoting conversational Latin called conventicula and rusticationes exist from Kentucky to West Virginia to Pennsylvania to Boston to Rome and elsewhere. We have seen in the case of the direct method that a significant obstacle to a communicative approach is teacher proficiency. Those who wish to incorporate spoken Latin in the classroom would do well to partake in programs like these. The revival of spoken Latin renews the question of whether Latin should be allowed to evolve (cf. Medieval Latin) or retained in its classical form (cf. Neo-Latin). For one answer to the question, see Owens 2016.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed the pedagogical landscape broadly not least by normalizing remote learning. Whether they liked it or not, teachers experimented with new modalities (fully online and hybrid, synchronous versus asynchronous) and digital learning tools that work more or less. Texts have increasingly shifted from traditional print, where it may take years for materials an author currently uses to become available for others, to Open Educational Resources (a fancy name for a website), where they can be published instantaneously, and self-published short stories called novellas. The latter have become particularly popular in high school Latin classes. Here are two pages from Justin Slocum Bailey’s Latin translation of Carol Gaab’s Brandon Brown Quiere un Perro:

So far the 21st century has been an age of eclecticism. With easy access to what sometimes feels like a bottomless pit of resources, and plenty of ideas for new ones, even the traditional classroom is looking beyond the textbook for supplements more than before. More experimental classrooms have already thrown textbooks out the window.

It often seems to be the case that at any given moment Greek and Latin pedagogy has just caught up to where the modern languages were several decades prior. Whether premodern languages should follow the pedagogy of modern languages is the topic of another discussion. The modern languages are now transitioning to a post-textbook world where each classroom reflects the pedagogical miscellany of a particular teacher or language program director. The Greek and Latin classroom seems to be headed in that direction as well, following in the footsteps of their modern counterparts faster than usual.

Bibliography

Aleandro, G. 1532. Elementale introductiorum in nominum et verborum declinationes graecas. Hero Alopecius.

Allen, W. S. 1987. Vox Graeca. 3rd edition. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 1989. Vox Latina. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press.

American Classical League. 1924. The Classical Investigation, Part One. Abridged Edition. American Classical League.

Andrews, E. A. 1864. First Lessons in Latin. 40th edition. Crocker & Brewster.

Appleton, R. B. & Jones, W. H. S. 1916. Initium; a First Latin Course on the Direct Method. Cambridge University Press.

Balme, M. & Lawall, G. 2016. Athenaze. 3rd edition. Oxford University Press (Italian edition 2013, Edizioni Accademia Vivarium Novum).

Balme, M. & Morwood, J. 1987. Oxford Latin Course. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2012. Oxford Latin Course, College Edition. Oxford University Press.

Bennett, C. E. & Bristol, G. F. 1903. The Teaching of Latin and Greek in the Secondary School. Longmans, Green, and Co.

Botley, P. 2010. Learning Greek in Western Europe, 1396-1529: Grammars: Lexica, and Classroom Texts. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 100.2.

Briggs, Jr., W. W. No date. “Gildersleeve, Basil Lanneau.” Database of Classical Scholars. Rutgers.

Brinsley, J. 1612. The Posing of the Parts. Thomas Man.

Cambridge School Classics Project. 2015. Cambridge Latin Course. 5th edition. Cambridge University Press.

Camden, W. 1595. A Greek Grammar for the Use of Westminster School. G. W. Ginger.

Carey, C. 2015. “Attic Orators. Oxford Classical Dictionary Online.

Castle, M. 2023. “History of the Jenney Latin Series (1953-1990): A Review of a Latin Program for Language Learners.” Website.

Cheever, E. 1708. Accidence. Boston [uncertain].

Chickering, E. C. 1912. “The Direct Method in Latin Teaching.” Classical Quarterly 6.5: 34-37.

Chrysoloras, M. 1471? Ἐρωτήματα. Venice: Adam de Ambergau.

Com(m)enius, J. A. 1659. Orbis Sensualium Pictus. C. Hoole (trans.). London [uncertain].

Cothran, M. 2011. “The Classical Education of the Puritans.” Webpage.

Crane, G. 2015. “Bad News for Latin in the US, Worse for Greek.” Webpage.

Crosby, H. L. & Schaeffer, J. N. 1928. An Introduction to Greek. Allyn and Bacon.

Dickey, E. 2016. Learning Latin the Ancient Way: Latin Textbooks from the Ancient World. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2018. Learn Latin from the Romans. Cambridge University Press.

Dugan, K. P. 2019. “The ‘Happy Slave’ Narrative and Classics Pedagogy: A Verbal and Visual Analysis of Beginning Greek and Latin Textbooks.” New England Classical Journal 46.1: 62-87.

Ellis, D. 2008. The Study of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford University Press.

Erasmus, D. 1528. Dialogus de recta Latini Graecique sermonis pronuntiatione. R. Stephanus.

Gaab, C. 2016. Brando Brown Canem Vult. Justin Slocum Bailey (trans.). Fluency Matters.

Ganss, G. 1954. Saint Ignatius’ Idea of a Jesuit University: A Study in the History of Catholic Education, Including Part Four of the Constitutions of the Society of Jesus. 2nd edition. Marquette University Press.

Gildersleeve, B. L. 1879. A Latin Primer. University Publishing Company.

—————. 1885. A Latin Primer. Revised edition. University Publishing Company.

Goldin, C. & Katz, L. F. 2008. The Race between Education and Technology. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Groton, A. H. 2013. From Alpha to Omega: A Beginning Course in Classical Greek. 4th edition. Hackett.

Hands Up Education. 2020-2025. Suburani. Hands Up Education.

Hansen, H. & Quinn, G. M. 1992. Greek: An Intensive Course. 2nd revised edition. Fordham.

Honey, M. T. 1939. “The Classics in America.” Greece & Rome 9.25: 36-42.

Horrocks, G. 1997. Greek: A History of the Language and its Speakers. Longman.

Jenney, C., Scudder, R. V., & Baade, E. C. 1985. Jenney’s First Year Latin. Prentice Hall.

Jensen, S. R. 2018. “The Reception of Sparta in North America.” In A. Powell (ed.), A Companion to Sparta. Wiley Blackwell: 704-722.

Jones, E. 1882. First Lessons in Latin. S. C. Griggs and Company.

Joint Association of Classical Teachers. 1978. Reading Greek: Grammar and Exercises. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 1978. Reading Greek: Text and Vocabulary. Cambridge University Press.

Keller, A. & Russell, S. 2004. Learn to Read Latin. Yale University Press.

—————. 2012. Learn to Read Greek. Yale University Press.

Kelley, B. M. Yale: A History. Revised edition. Yale University Press.

Kirtland, J. C. 1913. “The Direct Method of Teaching the Classics: The Availability of the Method for American Schools.” The Classical Journal 8.9: 355-363.

Lewis, C. T. & Short, C. 1879. A Latin Dictionary. Harper and Brothers.

Liddell, H. G., Scott, R., Jones, H. S., & McKenzie, R. 1843. A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford University Press.

Lily, W. 1544. An Introduction to the Eyght Partes of Speche, and the Construction of the Same. Thomas Berthelet.

Lusin, N., Peterson, T., Sulewski, C., & Zafer, R. 2023. Enrollments in Languages Other Than English in US Institutions of Higher Education, Fall 2021. Modern Language Association of America.

Marrou, H. I. 1956. A History of Education in Antiquity. Sheed and Ward.

Mastronarde, D. J. Introduction to Attic Greek. 2nd edition. University of California Press.

Minkova, M. & Tunberg, T. 2008-2009. Latin for the New Millennium. 2 volumes. Bolchazy-Carducci.

Mintz, S. 2022. “How the 1960s Created the Colleges and Universities of Today.” Inside Higher Ed.

Monat, P. 1993. Review of Hans H. Ørberg, Lingua Latina per se illustrata. Pars I. Familia Romana et Pars II. Roma aeterna. Latomus 52.1: 239-240.

Moreland, F. L. & Fleischer, R. M. 1977. Latin: An Intensive Course. University of California Press.

Morgan, G. 1976. Lexis. Revised edition. Gareth Morgan.

Morison, S. E. 1935. The Founding of Harvard College. Harvard University Press.

Most, W. G. 1962. Teacher’s Manual for Latin by the Natural Method (First and Second Year). Revised edition. Henry Regnery Company.

Ørberg, H. H. 1991. Lingua Latina per se illustrata, Pars I: Familia Romana. Focus.

Owens, P. 2016. “Barbarisms at the Gate: An Analysis of Some Perils of Active Latin Pedagogy.” Classical World 109.4: 507-523.

Patterson, J. F. 2021. Gareth Morgan’s Lexis. Greenbelt Press.

Paul, J. 2013. “The Democratic Turn in (and through) Pedagogy: A Case Study of the Cambridge Latin Course.” In Classics in the Modern World: A Democratic Turn? Edited by L. Hardwick and S. Harrison. Oxford University Press: 143-156.

Peckett, C. W. E. & Munday, A. R. 1070. Thrasymachus: A New Greek Course. Revised edition. Wilding and Son Ltd.

Rigg, A. G. 1996. “Medieval Latin Philology.” In F. A. C. Mantello & A. G. Rigg (eds), Medieval Latin: An Introduction and Bibliographical Guide. Catholic University of America Press: 71-78.

Robinson, E. 2017. “‘The Slaves Were Happy’: High School Latin and the Horrors of Classical Studies.” Eidolon.

Rouse, W. H. D. & Appleton, R. B. 1925. Latin on the Direct Method. University of London Press.

Scottish Classics Group, The. 1971. Ecce Romani. Oliver & Boyd.

Sebesta, J. L. 1990. “Textbooks in Greek and Latin: 1990 Survey.” The Classical World 83.3: 171-219.

Shelmerdine, C. 2020. Introduction to Greek. 3rd edition. Focus.

Shelmerdine, S. 2013. Introduction to Latin. 2nd edition. Focus.

Smith, M. L. 1913. Latin Lessons. Allyn and Bacon.

Stray, C. 2007. “Education.” In A Companion to the Classical Tradition. C. W. Kallendort (ed.). Wiley-Blackwell: 5-14.

—————2011. “Success and Failure: W.H.D Rouse and direct-method Classics teaching in Edwardian England.” Journal Of Classics Teaching 22: 5-7.

U.S. Department of Education. 1993. 120 years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait. U.S. GPO.

Ullman, B. L. 1925. “The Classical Investigation.” The Journal of Education 102.2: 48-49.

Weale, S. 2022. “UK school Latin course overhauled to reflect diversity of Roman world.” The Guardian.

Wheelock, F. M. 1956. Latin: An Introductory Course for College Students Based on Ancient Authors. Barnes & Noble.

Wheelock, F. M. & LaFleur, R. A. 2011. Wheelock’s Latin. 7th edition. HarperCollins.

Woods, M. C. 2019. Weeping for Dido: The Classics in the Medieval Classroom. Princeton University Press.

Ziobro, W. No date. “Latin in Early America: An Anthology of Readings in 17th and 18th Century Latin for Post-Intermediate Level Latin Students.” Website.

—————. 2011. “Classical America.” Revised. Website.